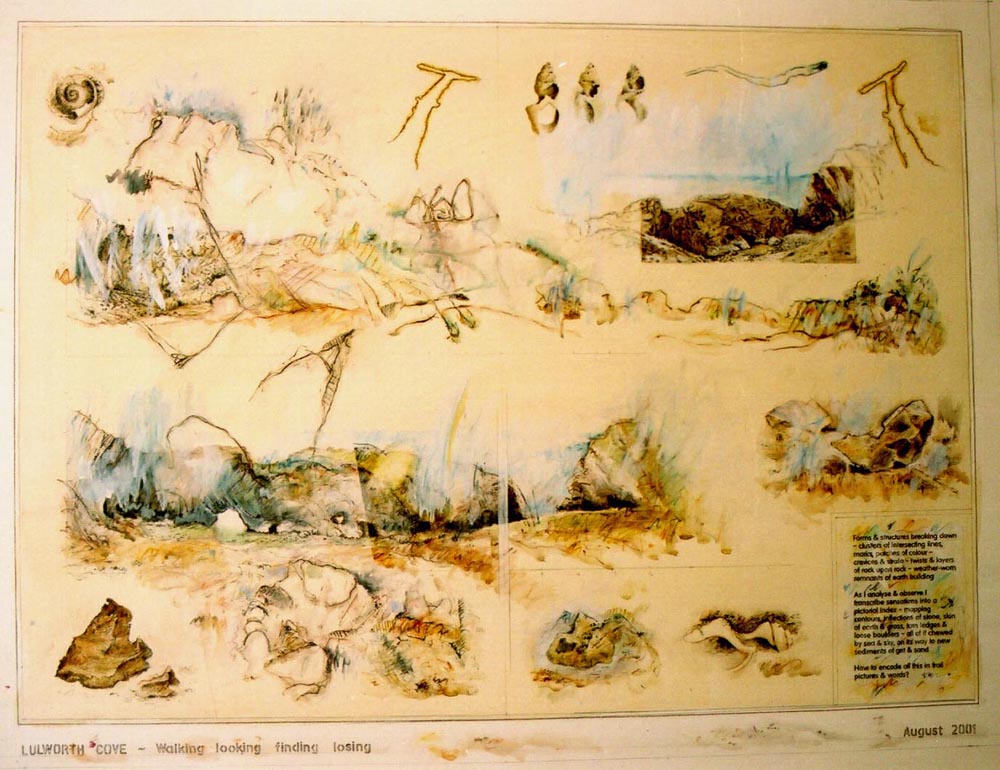

In the Autumn of 2001 I presented an exhibition at Dorset County Museum, Dorchester, entitled Dorset Fragments. Here are a few of the works that were included:

Flatstone study

Flatstone study

Skulleye study

Skulleye study

Small flint study

Small flint study

Robyn Davidson, the author of Tracks (1980) wrote an introduction to the exhibition which gives a useful perspective on my work at the time:

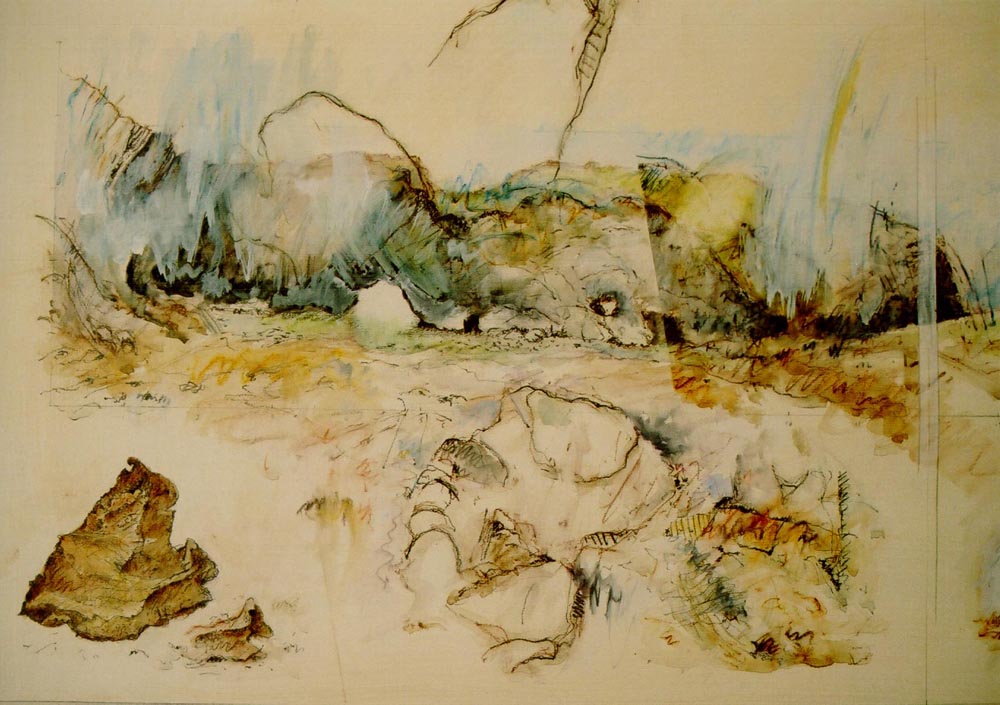

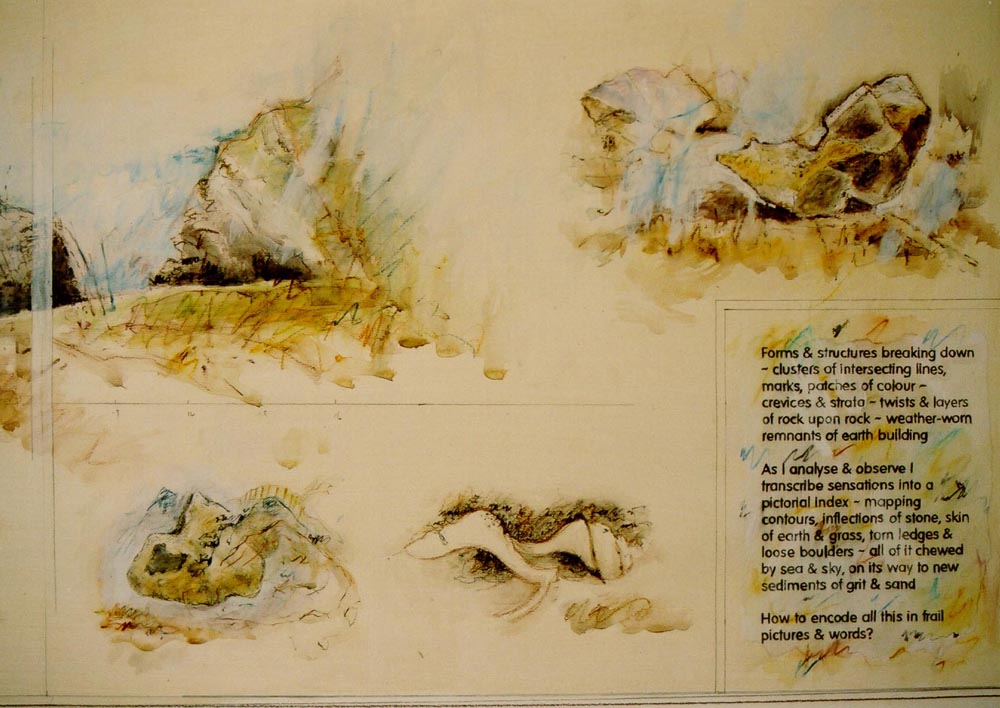

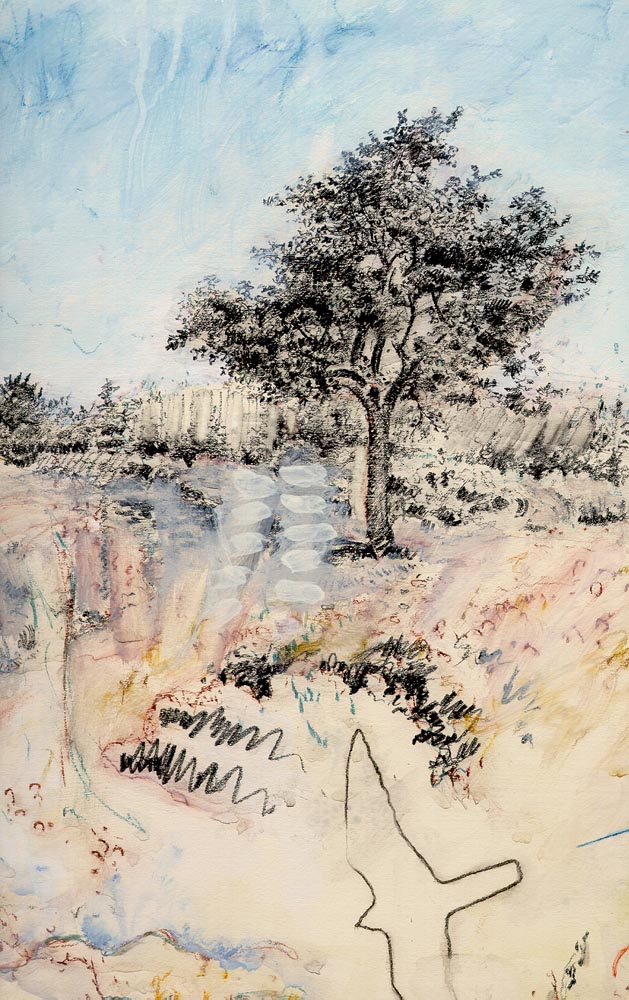

A Note on the Paintings At first glance, you might think these pictures had been made by a 19th century explorer – a naturalist, geologist, cartographer – observing nature’s ‘data’ from the position of an outsider. He would be a man formed by the idea that observer and observed, man and nature, are separate from each other, as if consciousness had somehow parachuted into the material world from elsewhere.

But a second look reveals that these references to a previous sensibility are being challenged to the point of erosion. The still timelessness of profound scrutiny and the attention to objects which seem to be permanent, is counterposed against the transitory nature of all things, mere glimmers and fragments of forms in time, ever decaying, ever emerging. It is this that twists the paintings out of the 19th century and places them squarely in our own, more anxious, time. As human consciousness becomes an object of enquiry to itself, consciousness as a fixed entity is seen to dissolve, to be rooted nowhere, to be impermanent – an idea which is not dissimilar to Eastern philosophies of egolessness. Mind and nature are not separate, but are embedded together. Mind/nature is ephemeral. The notion of a fixed self is being questioned, both in philosophical discourse and by hard science. The desire to ‘imitate nature in her manner of operation,’ as John Cage put it, is not so very far from a 19th century sensibility, but how we conceive of her ‘manner of operation’ and where we place ourselves in relation to that operation, have profoundly altered.

John’s paintings evoke, for me, that tension between the truth of flux, and our human longing to make solid what is essentially impermanent. They are also, necessarily, about time and memory. Historical time is treated as a kind of geology – layers of previousness are revealed then buried again. And we ourselves are made of memory, a ‘frail torn fabric’.

As we move across the picture surface, forms come in and out of view, grab our attention, fade. It’s as if we were reading maps or records, not just of what we perceive, but of how we perceive. There is a tension between open fields of Turneresque colour and light, and the intense observation of nature’s detail, requiring us to step back and to come forward. The paintings unpack their compressed time in our scrutiny of them.

The materials he uses are simple; the means, minimal. Paper, water, some earth, a stub of graphite – what any explorer might have to hand, and not much more than a Paleolithic artist might have to hand. We are reminded that it is the nature of being human to make marks, in an attempt to understand the elusiveness and mystery of things and of ourselves.

Robyn Davidson, writer & traveller. September 2001.