In my first book I brought together various themes and strands of thought that I’d been pursuing over the preceding few years. Published by Rodopi, 2006. Here’s the blurb from the book, which gives an idea of what it is about.

In this book the author takes an unusual multi-disciplinary approach to debates about contemporary art and poetry, ideas about the mind and its representations, and theories of knowledge and being. Arts practices are considered as enactments of mind and as transformative modes of consciousness. Ideas drawn from poetics, philosophy and consciousness studies are used to illuminate the conceptual and aesthetic frameworks of a diverse array of visual artists. Themes explored include: the interconnectedness of existence; art as a way of interrogating appearances; identity and otherness; art and the self as ‘open work’; Buddhist concepts of ‘emptiness’ and ‘suchness’; scepticism, mysticism and the arts; and mind in the landscape. The book contains an important and distinctive visual dimension with photographs and drawings by the author and texts employing unorthodox syntax and layouts that exemplify the themes under discussion. The author hints at a new aesthetics and philosophy of indeterminacy, paradox, uncertainty and discontinuity – a contrarium – in which we negotiate our way through the instabilities and contradictions of contemporary life. Written in a lively and accessible style this volume is of interest to scholars, arts practitioners, teachers and to anyone with an interest in art, poetry, consciousness studies, philosophy and nature.

Artists, poets and philosophers discussed, include: Cy Twombly, Helen Chadwick, John Ruskin, Ad Reinhardt, Richard Long, James Turrell, Anish Kapoor, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Agnes Martin, Land Art, Arte Povera, Minimalism, Charles Olson, Kenneth White, Robin Blaser, Fred Wah, Gary Snyder, RS Thomas, John Cage, Jorge Luis Borges, Guy Davenport, Kenneth Rexroth, Heidegger, Marjorie Perloff, Thomas McEvilley, Merleau-Ponty, Spinoza, Wittgenstein, Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco, David Abram, Thomas Merton, Pyrrho & Nagarjuna.

To read reviews of Picturing Mind, click here.

Here are a few extracts from Picturing Mind (without the references):

From the Introduction:

An opening, an entering

It is a misty late January day and the first white camellias are just coming into bloom. A blurred penumbra of light hovers about the delicate petals, faint emblems of a springtime yet to come. As I walk I think of the book just beginning and my thoughts are as scattered as the torn strands of bark that litter the shadows beneath a pair of eucalyptus trees swaying elegantly in the breeze. All around me there is birdsong, sounds of moisture dripping from high branches and the occasional bark of a dog. These sensations and scattered thoughts form unique patterns that exist for a moment and then dissolve one into another. Each pattern is a moment of becoming, a shifting current of attentiveness and engagement that, for loss of a better word, I call my “self”.

This book is made out of many such patterns. It charts an unfolding of thoughts and images within a dynamic sensory field that is complex and ever-changing. To make some kind of constancy out of inconstancy is an ancient human endeavour, linking us to palaeolithic ancestors who first took spit and charcoal to inscribe their presence on the walls of dark caves. Just as those early glyphs and drawings were superimposed upon each other in a layered history of doing, knowing and being, so this book is a layered history of ideas, images, beliefs and questions.

Seen in another way the book represents a particular topography of mind, a particular way of picturing and thinking about the world in which I am a temporary participant. Ideas about practices in art and poetry are interwoven with reflections on philosophies of art and poetics. Occasionally another strand comes to the surface: thoughts about ways of learning and teaching in the arts. These linear narratives are punctuated by a more poetic non-linear discourse that includes experimental texts, drawings and photographic images.

The book is organised in a way that emphasises the interdependence of these strands and in a way that reflects the sudden shifts of awareness and thought. I realise that it may be seen as a distant cousin of the medieval tradition of the florilegium, a collection of extracts from many sources put together in a way that is like a bunch of flowers. G.R. Evans mentions that Clement of Alexandria compares his own collection, Miscellanies (Stomateis), to the diversity of flora in a meadow, each flower and grass contributing a distinctive form, colour and tone to the variegated field. I like the idea of the page as a field of diverse texts and images, each one having its own distinct morphology, a collection of voices speaking with varied rhythms, diction and point of view. Within this collectaneum miscellaneum, many themes, ideas and strands of argument are presented as a mosaic or scrapbook, from which we draw our own conclusions, make our own chain of connections (concatenatio) and encounter with surprise unexpected juxtapositions and discontinuities. Maybe Robert Duncan is referring to, and extending, this medieval tradition in his own poetics, arguing in favour of the poem as a “melee” rather than “a synthesis”, the poem as a field of many voices. I hope the present volume will be considered in a similar way.

And from Part 4, The mutuality of existence: drawing, emptiness & presence:

Still-life, again

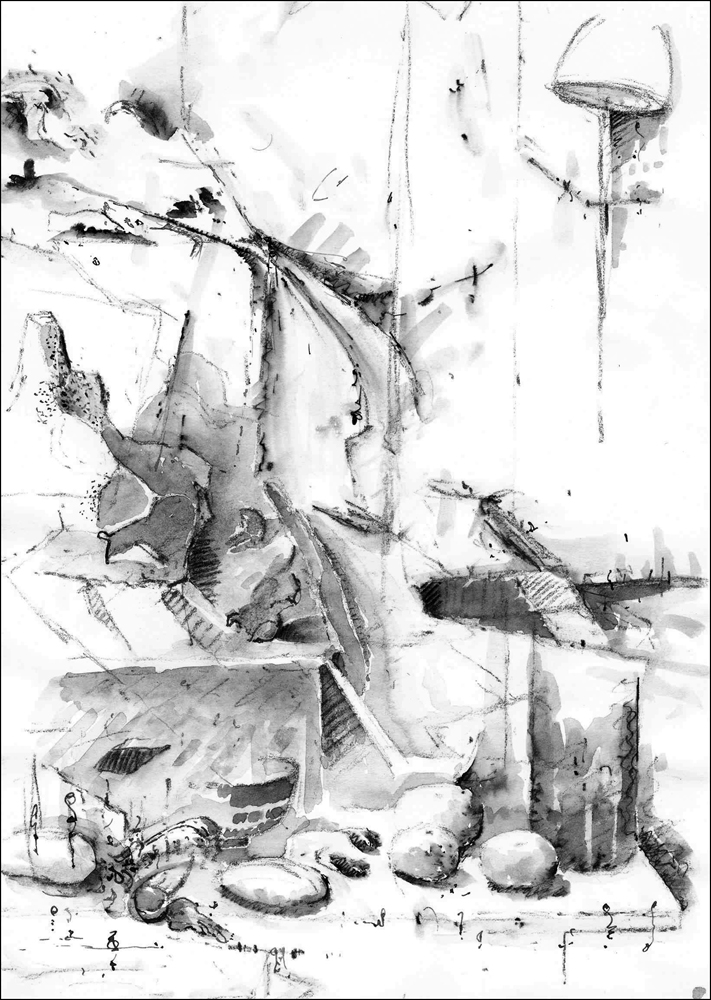

Once again I’m looking at the same set-up of still-life objects. On this occasion I’m not drawing. I’m using words to describe what is before me. I see a deer skull, various stones, bones and flower-heads with stalks. I notice that the stones are of three kinds: large smoothly-rounded pebbles from a nearby beach; flat flakes of shale dug up from the garden, sharp-edged and dull brown in colour; and lots of small gravelly stones in shades of ochre, brown and grey. The large rounded pebbles are either evenly mottled or marked with distinctive shapes, often deep purple-grey against pale blue-grey. The skull is broken. A large part of one side is missing. Sharp edges catch the light against the shadowed recess of the missing side. Pieces of jawbone are lying flat in front of the skull. I notice another smaller skull, pale and finely-formed, to the left and behind the large one. I wonder what kind it is. The dried-up flower heads and attached stalks belong to a large poppy. They look brittle and contorted. These objects lie on a rectangular horizontal surface, draped in a canvas that is attached to the wall behind. The canvas is stained in brown and reddish patches, with bold dark-grey leaf shapes printed here and there, and small chevrons arranged in double lines around a square. A bag hangs to one side. A tall lamp casts bold shadows. The whole arrangement is against one wall of a studio room that contains many other objects in stacks, on shelves and in trays.

The words I’m using are tokens of things, conceptual labels classifying what I see into categories that can be used for many quantitative and qualitative processes of description, analysis, narrative and speculation. Thinking linguistically in this way is a very different process to the process of drawing. We use each process to do different things and each process exemplifies a different state of consciousness, and different ways of knowing and being in the world.

In both drawing and wording, in representing my perceptual activity in marks and words, I become aware of relationships that bind together my perceptions and the “things” I’m looking at. My movements change the field of vision. What I see is conditioned to some extent by what I’m looking for, as well as what I’m looking at. The objects in front of me are also perceptual events, changing patterns of light filtered and processed by an embodied mind. The observer is intimately implicated in what is observed.

As I sit looking at the still-life I realise that it is anything but “still”, rather it is a dynamic network of relationships that constantly shifts and reorganises itself as I change my position spatially and cognitively. I notice how my glance moves backwards and forwards, left and right, up and down. I scan the field of vision in a continuous dance of attention, shifting seamlessly from detail to detail within an emergent whole. In this complex field I can focus on particular objects or details but I can never shut out the immediate surroundings. Indeed I realise that each object is an integral part of its surroundings. Without its surroundings it would be infinite in size or extension, or it would not exist. Object and surroundings, figure and ground, are mutually existent. They arise together or not at all.