Buddhism and art: modes of enquiry and awakening. 2006.

– an introductory talk on Buddhism and art given to undergraduate students as part of a course on the relationship between philosophical ideas and art practice.

Introduction

I ought to say at the beginning that it is impossible in a short (or long) talk to do justice to the varied and extensive field of thought and practice that we call Buddhism. Buddhism is as varied as any of the major religions in its cultural forms, beliefs and values – ranging from the highly ornate art and ritual of Tibetan Buddhism, to the traditions of forest monks in Thailand and Cambodia, to the Quaker-like simplicity of Zen Buddhism in China, Japan and Korea. My background is in the Soto practices of Zen Buddhism (for over 45 years!) – therefore my articulation of Buddhist ideas and values is grounded in my practice within one strand of its many traditions.

Buddhism, unlike the other major religions (except, Daoism) is non-theistic – it is not a God-centred belief system – despite the fact that some schools of Buddhism emphasise faith and all schools treat the Buddha with great reverence (except Zen – on occasions). The Buddha is not a God, nor is he an intermediary between Buddhists and God.

The Buddha’s life: one version of the story

At the heart of Buddhism is the story of one man’s experience of the essential difficulties of human existence, his analysis of these conditions and his realisation of a way of living with these conditions. A typical version of this story goes like this: the Buddha was born as Siddartha Gotama, around 623 BC. He was the son of a rich minor ruler of a small Indian state. He died around 545 BC (this makes him a contemporary of the earliest Greek philosophers like Pythagoras). In his early life he was kept free of contact with all aspects of suffering. As a young man he left his palace enclosure for the first time. As he began to explore the world outside the palace walls he met an old man “suffering from the ravages of age, an invalid bearing the marks of his disease, a corpse being carried to cremation, and a monk seeking salvation”. The shock of these encounters changed his life. He realised that ageing, sickness, suffering and death were integral features of human existence and somehow he had to come to terms with these facts.

Even though he had married and had a son, Siddartha left his home and vowed to search out a path to understanding and liberation from the chains of suffering. He experienced extremes of sensuality and asceticism, studying under every master he could find – but to no avail. Finally, even though by now he had his own disciples, he sat down under a banyan tree (fig or Bo tree – after Bodhi: bliss) and vowed not to get up until he had solved the great problem of his life. At the age of 35, he attained enlightenment or liberation, and ate a good meal after having taught his disciples the importance of taking as little food as possible! He became known as Buddha, ‘the enlightened one’, and from then on he taught the ‘middle way’ (between extremes), as a path to enlightenment for others. He wrote nothing and always urged his followers to question everything that he and other teachers said, and to test everything against their own experience: ‘To thine own self be true’.

This emphasis on experiential enquiry became a key tenet of Buddhism – and Buddhism can be seen as a set of practices, ideas and values tested over many hundreds of years by generations of individuals who have experienced the great conundrums of life – often by sitting (meditation) as the Buddha had done.

Buddhism & Hinduism

The historical Buddha (Shakyamuni) lived within a Hindu society (although Hinduism is a 19th century collective term for the multitude of sects and beliefs that make up Indian religious culture) which emphasised: re-incarnation (life-after-life); samsara – no escape from the wheel of life-death-rebirth; powered by karma – the inevitability of all actions having consequences (largely seen as negative). At the centre of this worldview was a belief in the concept of atman – the essential self or soul, an entity that continues through life after life.

The Buddha’s experience of observing his mind in tranquillity led him to argue against these beliefs. He taught that re-incarnation was a moment-by-moment process (ref. contemporary consciousness studies), that release from samsara was possible, and that karma could be seen as a positive law – enabling us to benefit from ‘right action’ and ‘right thinking’. Most importantly his years of watching the mind led him to believe that there was no essential self or soul (atman) – instead he argued for the idea of anatman (Sanskrit) or anatta (Pali) – no continuing essence or self. This was a huge challenge to the culture within which he lived, something that most of his contemporaries and succeeding generations couldn’t accept – and it may be one of the main reasons why Buddhism gradually diminished in India. The Buddha often used the metaphor of life being like a flame that was passed from one candle to another – there is no continuing essence only a process of endless chemical change. This process is referred to as anitya or impermanence.

The Four Noble Truths

The insights of the Buddha came to be formulated as the Four Noble Truths:

- Suffering, dukkha, exists: ‘Birth is suffering, ageing is suffering, pain, grief and despair are suffering’. Alongside these forms of suffering are the endless dissatisfactions and discontents of everyday life – the frustrations and irritations that disturb our tranquillity and balance.

- Suffering, in all its forms, is mostly caused by craving, clinging or desire (trishna) – attachment to what is impermanent, constantly changing or passing away. We tend to desire things or states of being or qualities that we don’t currently have (more money, beauty, success). We seek to hold on to things or states that are always changing (beauty, happiness, contentment). If all things have no essence or fixed identity how can we hold on to them? Why do we desire or attach ourselves to what is always changing and passing away? We do this because we are in a state of ignorance, avidya. This is the opposite of awakening or enlightenment. We are deluded into believing in the illusion of permanence – the illusion that the candle flame has a fixed essence.

- The Buddha argues that there is a way out of this maze of dissatisfactions. It is possible for any of us to experience the way things are – to realise what is going on – and to escape from the endless cycle of trying to hang on to what is always changing or flowing away from us. By letting-go of things that can’t be grasped or hung on to, we lessen our suffering and escape the wheel of samsara – we can become enlightened!

- The forth truth is a path or recipe for how to achieve enlightenment: right thinking; right action; etc. A path of ethics, meditation and knowledge. Upaya – skilful means.

All Buddhist schools and practices are based on these principles – though they take many different forms depending on their cultural context. Buddhism in Europe and America is only the latest in a series of migrations from India to Tibet, China, Korea and Japan (Mahayana Buddhism: Tantra, Ch’an, Zen, etc), and from India to Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia and elsewhere in south-east Asia (Theravada Buddhism).

Enlightenment & compassion

En-lighten-ment can be seen as having three strands of meaning:

- To shed light on

- To understand & be wise

- To have one’s burden lightened – eg. the burden of delusion, desire & attachment.

Also there may be links to Heidegger’s notion of Dasein: ‘being there’ – being as an opening or clearing in which possibilities arise.

Although the state of enlightenment sounds high-flown and beyond ordinary human capabilities – in many schools of Buddhism it is not seen like that. Whereas Theravada Buddhism tends to see enlightenment as a gradual process, the result of faith, ritual and incremental change in behaviour and thought, Mahayana Buddhists tend to believe in the possibility of sudden insight (satori, kensho), at many levels, that can occur in the everyday lives of monks and lay people. In the Zen schools (Soto and Rinzai are best known in the west) the state of enlightenment is often referred to as: Buddha-mind, Original-mind, Beginner’s-mind, or the Unborn (Bankei).

It may seem like this emphasis on realisation is, in the end, very selfish and highly individualistic – it is too much about personal liberation. Buddhism recognises this danger and most traditions stress the importance of the Boddhisattva – a figure that crops up in Buddhist art almost as much as the Buddha. The Boddhisattva is someone who has attained the most perfect understanding, but who postpones their own enlightenment, the final casting off of self-delusion, in order to dedicate their life to the liberation of others. Compassion is seen as one of the most important virtues in Buddhism – metta: loving kindness. Boddhisattvas: Avalokiteshvara/Kwannon/Kannon – of mercy; Manjusri – of wisdom.

Emptiness of self-existence – sunyata

Within the Mahayana traditions the state of enlightenment is particularly characterised by a realisation of the ‘emptiness’ of existence (sunyata). That is, the fact that nothing exists by, and for, itself – all things are ‘empty’ of self-existence. Things only exist in relation to everything else that exists. Buddhists call this characteristic of existence, ‘mutual co-arising’ or ‘dependent origination’. Keep this in mind when we look at artworks which are often described as being about ‘emptiness’ – it is not the same emptiness as an empty glass or room. It is a way of pointing to the fact that there are no fixed identities or essences to things – including ourselves – indeed there is no fixed, essential ‘self’ or soul, only a ceaseless process of being or becoming.

In Buddhism the self is often described as being a heap or bundle of aggregates (skandhas) that come together on a temporary basis – like all phenomena they come and go – our ‘self’ is a temporary manifestation of these skhandas arranged in a particular pattern that is constantly changing (reminiscent of Cezanne’s statement: “we are a shimmering chaos”). The five Skandhas consist of: forms of matter (rupa); apperception or sensory awareness: by sight, sound, smell, touch, taste + mental objects; perception of external environment; volition or will, the basis of emotions; and consciousness. [There may be parallels with current neurological theories of consciousness]

*

Buddhist ideas & insights & art

I’m now going to focus on some manifestations of these Buddhist principles and insights in a variety of artworks and art practices. I’m not suggesting for a minute that these are examples of Buddhist art. In some cases I’m tracing affinities of intention or idea, in some cases there is evidence of the direct influence of Buddhist insights or principles, and in some cases the works are made by Buddhist practitioners – who may, or may not, consider what they do to be enactments of Buddhist practice.

Impermanence, evanescence, flux – Anitya

Cezanne: “We are a shimmering chaos”.

In Monet’s series of paintings of Rouen cathedral seen at different times of day, we see the artist grappling with the fugitive qualities of sensation and experience. What we see is constantly shifting – arising and passing away from our field of vision. As all phenomena arise and decay in our consciousness – like sparks from a fire glowing in the darkness before they become part of the darkness. Much of Monet’s work, and the work of the other Impressionist’s is, at one level, a meditation on impermanence. We get a sense of the brevity of passing events and sensations, and of life itself. The painter tries to fix the everchanging sensations that flicker in his consciousness, fixing them in pigment on canvas. Yet Monet (and Cezanne particularly) constantly remind us that this is an impossible task and their images are full of poignancy and incompleteness – as if the task of representation is always a chasing after clouds or ghosts. The rigour with which Cezanne and Monet set about their task is very reminiscent of the Zen attitude to zazen or sitting meditation. [more later]

In the Waterlilies paintings, done late in his life, Monet continues with his attempt to record passing sensations of light and colour, but alongside this is the use of the waterlily motif as a metaphor for the struggle to find clarity and purity of vision, un-stained by attachments and preconceptions – just as the pure tones of the waterlily rise up out of the mud at its roots. It is likely that Monet saw echoes here of the imagery of Japanese prints. He was also well-versed in the symbolic culture of Japanese gardens, which he learnt from Japanese friends and gardeners.

In The Passing (video-1991) Bill Viola evokes the terrains of the conscious, the subconscious, and the desert landscapes of the Southwest – images of sleep, dreams and the drama of waking life merge into each other. Much of Viola’s work is about consciousness – what it is like to be alive, to be present, our being-in-the-world. It is also about the paradox that as we are alive we are also dying, each moment of consciousness is a moment of becoming in a field of being, a firing of neurons in the cosmic mind!!

Dove Bradshaw’s Indeterminacy series, consists, like many of her works, of objects and materials that undergo chemical change over time. This particular work consists of a small lump of pyrite rock placed on a much larger piece of Vermont marble. Placed out of doors, accessible to rain, the pyrite leaches chemical stains that spread in an indeterminate fashion over the marble. The process continues as long as the rocks are exposed to moisture. Transformation. Perpetual change. Eventually both rocks will erode & wash away – as we all do!

Attachment & non-attachment

Like in European memento mori, skulls crop up in Buddhist iconography as reminders of mortality – symbols of death and decay. In Buddhism they are also seen as reminders of the folly of becoming too attached to things and states (like success or wealth), somehow we need to remember that all things, feelings, hopes and fears pass away, and we should not treat them as if they were permanent or graspable. Often artists poke fun at our tendency to try to hang on to what will always slip through our fingers.

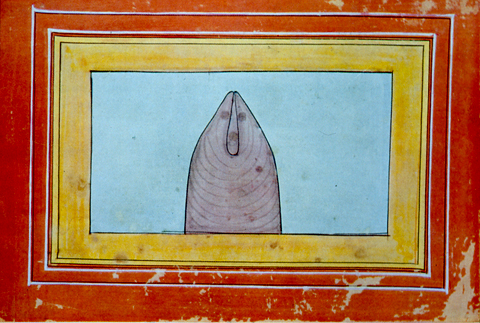

In Tantric Buddhism the human body is considered as both an aspect of the body of the cosmos, and as a microcosmic manifestation of the cosmic body/mind. So we find countless images of the structural relationships between the human body and celestial bodies like stars. In Tantric thought and practice the body in all its functions is both revered and accepted as a channel or vessel through which we can achieve enlightenment, and also as a passing phenomena that is always changing – something we should not and cannot hold on to.

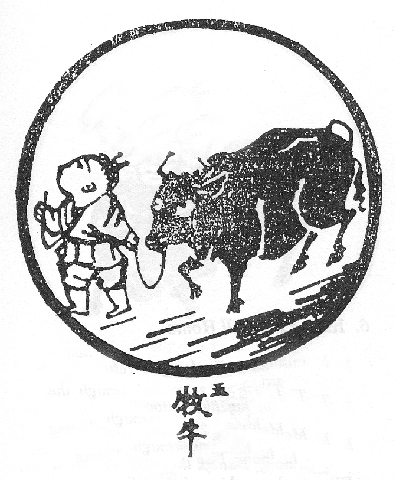

The 10 Bulls by Kakuan (Jap. 12th C) – is a story in ten episodes about the search for enlightenment. The bull becomes a symbol for life, the Tao or the Buddha-mind: 1 = search for the bull; 2 = discovering the footprints; …. to 5 = taming the bull; 8 = bull and self let go or liberated; 10 = back in the world – working for the liberation of others, the Bodhisattva path. Modern illustrations by Tomikichiro Tokuriki.

Emptiness, relativity, interpenetration – sunyata

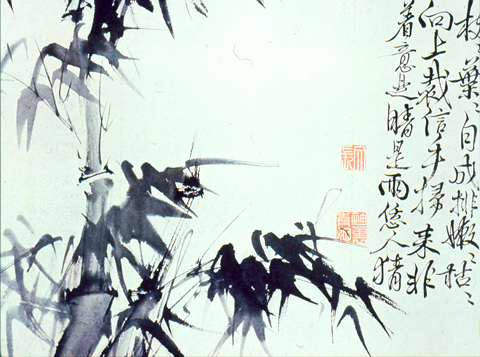

Sesshu (c.1420 – 1506) was a contemporary of Leonardo’s – a painter of great fluidity who epitomises the tradition of improvisatory brushwork. He became a Buddhist monk at age 11 or 12. He set out to forge Zen & painting into one practice. The name ‘Sesshu’ combines the characters for ‘snow’ and ‘boat’. He made a journey to China in middle-age. On his return he broke away from traditional Chinese models of landscape painting in favour of ‘direct’ experience of the vastness and structural complexity of nature. He was very influential on later Japanese artists. In Sesshu’s paintings each brush-stroke exists in relation to all the other marks within the open field of the picture surface. The interdependence of marks and ground is analogous to the interdependence of all of existence – the mutuality of being. The painting is a metaphor for, or an indexical sign of, the interrelatedness of everything – a sign of the lack of separateness or essences – emptiness or sunyata.

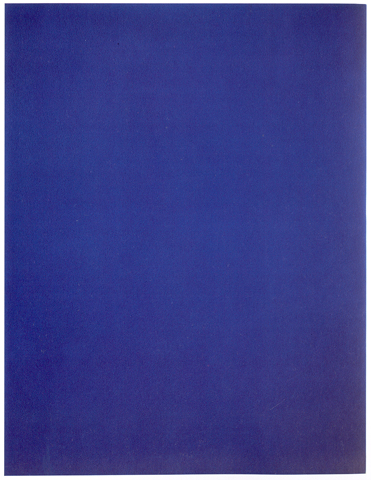

This is one of Yves Klein’s monochrome paintings – using Klein Blue. He was fascinated by Japanese culture – particularly martial arts. He became a black belt at Kadokan judo (ju = gentle, do = way). This painting can be seen as highly reductive formalism or as an ‘empty’ field in which forms and sensations flicker into life and die away – a dynamic ‘void’ within which forms arise and decay.

In 1962, the American painter, Ad Reinhardt writes: “The one thing to say about art is its breathlessness, lifelessness, deathlessness, contentlessness, formlessness, spacelessness, and timelessness. This is always the end of art”. (Smile of the Buddha, Baas, p.125) On another occasion he wrote: “The intensity, consciousness and perfection of Asiatic art comes from repetitiousness and sameness”. (ibid. 126) He argued that only “blankness, complete awareness, disinterestedness” constituted the right state of mind in which to make and engage with art. This may be the disinterestedness of Duchamp and of the Zen practitioner who sits just to sit. Reinhardt’s black or other monochrome paintings present us with our own act of looking for something. The dense yet subtly reflective surfaces resist our attempts to find a spatial bearing or an identifiable image within the pictorial field or a meaning within the semantic field. As with some of Kapoor’s works all we can do is perceive, experience the disorientation, give up trying to impose structure and meaning. Just as our attempts to solve a koan by rationalisation and intellectual means are doomed to failure, so we only come to terms with Reinhardt’s paintings by giving up our preconceptions and experiencing what is there. Reinhardt made an art of the list, and usually his lists and rules for making art, were lists of what not to do. A process of elimination or erasure, in the spirit of the Christian, Jewish and Islamic mystics who thought that only by naming everything in the universe would you be left with what was unnameable: that is, Yahweh or God. In one of his last lists, ‘Twelve Rules for a New Academy’, 1957 (ibid. 131) he writes at the end: “The fine artist should have a fine mind, free of all passion, ill-will and delusion”. It could be any Buddhist teacher speaking.

Koans & suchness – tathata

‘Joshu’s Mu’ is a koan often used in Rinzai Zen (Nantenbo had it as his first koan). Joshu, a Chinese Ch’an master, was asked by a monk: “Does a dog have the Buddha-nature”. To which Joshu answered, “Mu” (the Japanese for no or not) – despite the deeply held Buddhist belief that all beings have the Buddha-nature! This profound contradiction of everything most Zen monks are educated to believe, becomes an insoluble conundrum or koan – an untieable knot that monks struggle to untie logically, linguistically and symbolically. Time after time they return to the Zen teacher to give their response to the koan. Each time they are sent away. It is only when all possible solutions arrived at by rationalisation and the use of the categorising conventional mind, it is only when these have been discarded or given up that a realisation of Buddha-mind can occur – a kensho experience, a deep awareness of sunyata in daily life. All intentions, self-directed thoughts and actions, fall away. The conventional self and its drives and demands are let go of. For a while at least another way of doing, knowing and being arises that does not depend on attachment to things, essences, distinctions and dualities. When this is recognised by the Zen student and the teacher, often after many months, sometimes after years, the student is given another koan. The process continues. Somehow the mind ripens and flowers into what was always there but unrealised: the Buddha-mind. This process also involves a transformation of consciousness – so that the student becomes vividly awake to the present, to the actuality or ‘suchness’ of things.

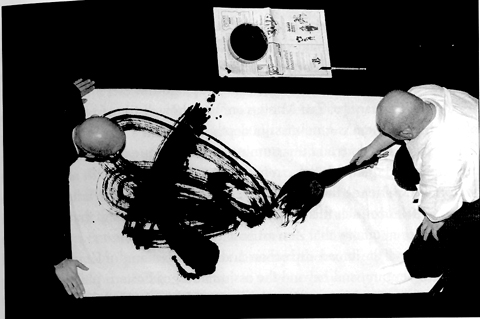

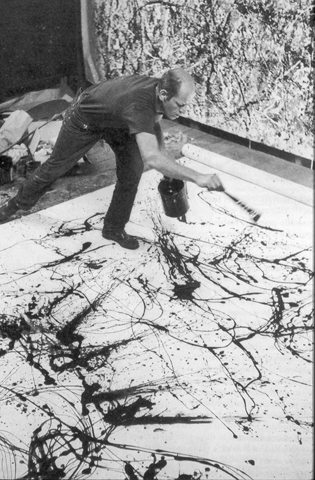

This quality of intense being-in-the-world – of presence – with no separation between body & mind, idea & action – is something that some of the American action painters talk about when describing their working method. A process they often liken to the improvisatory methods of jazz musicians who lose all sense of the separateness of self in the making of communal music. Somehow, they suggest, there is no sense of intention, will or predetermined plan, but only an unfolding of musical riffs and rhythms, in the stream of sound – just as Jackson Pollock becomes the act of painting, the gesturing embodied mind – leaving traces (indexical signs) of his existence in the material objecthood of the painting.

Awakening, realisation, en-lightenment, liberation – moksha

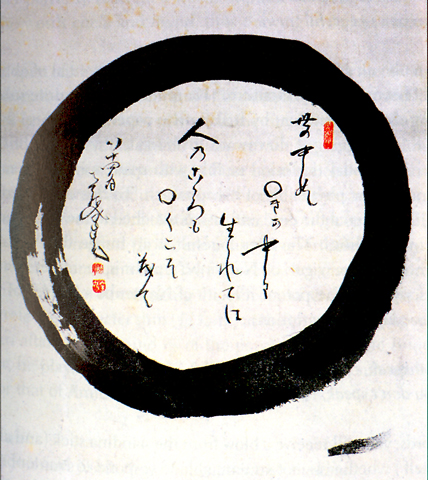

Enso (Zen circle) – symbolic of the awakened or enlightened consciousness, the Buddha-mind – but , more importantly, a manifestation or enactment of the non-self – a gesture of the embodied Buddha-mind – intentionless, yet focused, wide awake, acting yet not reacting – phenomena arise in the field of consciousness without comment and without grasping or desire. A significant action that does not signify. A presentation, rather than a representation.

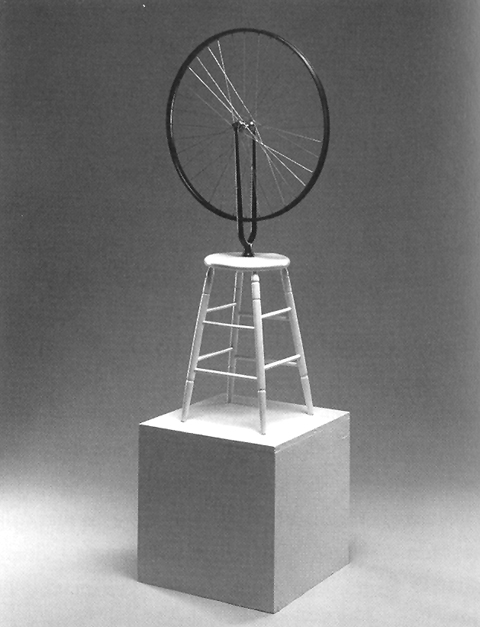

Duchamp was very interested in Buddhist ideas and strategies of awakening – maybe this can be seen in the iconography of the wheel (samsara) and in his provocative object/actions.

Many of Yoko Ono’s works combine the brevity of haiku poetry with the deadpan humour of Groucho Marx – she often points to the obvious, making it not-obvious – urging us to wake up to the everyday marvellous qualities of existence.

Basho’s famous poem – here translated by Dom Sylvester Houedard:

FROG

POND

PLOP

Just sitting – zazen, shikantaza

In Soto Zen, and in other Buddhist schools as practiced in the West, much emphasis is placed on sitting meditation, zazen or shikantaza – just sitting. In the Zen traditions this is a simple but difficult practice! It works on many levels. Most importantly it is a way of waking-up to this life – to being here. Being present and mindful. Being aware. Experiencing the flow of consciousness without commentary or without clinging – neither affirming or denying – just sitting.

Here is a famous Zen poem (from the Zenrin Kushu?):

When walking, just walk,

When sitting, just sit,

Above all, don’t wobble!

Issa (1763-1827):

Simply trust.

Do not the petals flutter down,

Just like that.

But, sadly, as Issa also writes:

A world of dew:

Yet within the dewdrops –

Quarrels!

Marina Abramovic has been a Buddhist practitioner for a long time. In the Nightsea Crossing works she and various other participants sit in silence on opposite sides of a table – often for seven hours a day. The gallery visitors see the two motionless figures – they can only guess at the flow of consciousness within and between the two figures. Abramovic talks about the intense shifting states of consciousness that she experienced in these pieces – similar to experiences she has had while in meditation.

In Waiting for an Idea we see Abramovic lying on a strip of wood with a piece of basalt under her head and a pile of marble rocks beside her. Will she have an idea before the rocks do? Do rocks have the Buddha-nature? Is this a koan?

Zuang Huan was born in China, emigrating to New York in the late 1990s. His performances tend to be physically very demanding – like lying naked on blocks of ice while surrounded by pet dogs (in China dogs are rarely kept as pets – they are animals or food). In Peace 1 he is suspended like a traditional wooden clapper for a large temple bell. The image is puzzling – a kind of sculptural koan – ‘what is the sound of one hand clapping’? What occurs in our minds as we engage with this work? What is the artist doing? How long will he be there? Is he a golden statue or a crazy man? What sound will occur when his head hits the bell? Will he be enlightened?

Nam June Paik (1932-2006): Born in Korea, educated in Japan and Germany. Paik met Cage at a New Music school in Darmstadt in 1958. Began making music/art performances under Cage’s influence – though Cage seemed unsure what to make of him! Once asked if he was a Buddhist, Paik replied, “No. I’m an artist”. In a series of works entitled TV Buddha he mocks the over-serious obsession of some Buddhists with meditation and the Buddha as ‘his holiness’, while also raising complex issues about awareness, cognition, representation and television as a cultural form. This work can be seen as a contemporary equivalent of Sengai’s, Meditating Frog.

Sengai Gibon (1750-c.1837) wasn’t a professional artist, he was a Rinzai Zen monk and teacher – the abbot of Shofukuji temple (the oldest Zen temple in Japan – founded by Eisai – who brought Zen to Japan – in the 12th century). This image is both an affectionate evocation of the physical activity of zazen, and a witty comment on the folly of becoming attached to the act of sitting – as if this will cause or lead to enlightenment (satori). According to many Zen masters no amount of desiring satori will lead to enlightenment – we have to sit without expectation or desire, only then does the goalless goal of satori happen. Sengai often used his hundreds of ink drawings as teaching aids – pointing the way.

Zen teacher, Ikkyu, summed up this old life of ours in the following way:

We eat, excrete, sleep, and get up;

This is our world.

All we have to do after

That – is to die.

Brief bibliography (some of these texts may be difficult to find!)

Armstrong, K. (2006) The Great Transformation: The World in the Time of Buddha, Socrates, Confucius and Jeremiah, London: Atlantic Books

Baas, J. & Jacob, M.J. eds. (2004) Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press

Baas, J. (2005) Smile of the Buddha: Eastern Philosophy & Western Art from Monet to Today, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press

Batchelor, S. (1990) The Faith to Doubt: Glimpses of Buddhist Uncertainty, Berkeley, USA: Parallax Press

Brown, K. (2000) John Cage Visual Art: To Sober and Quiet the Mind, San Francisco: Crown Point Press

Dreyfus, G.B.J. (2003) the sound of two hands clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhis Monk, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press [scholarly account of Tibetan Buddhist education & training for practice]

Ginsberg, A. (1968) Angkor Wat, London: Fulcrum Press

Gunaratana, B.H. (2001) Eight Mindful Steps to Happiness: walking the Buddha’s path, Boston, USA: Wisdom Publications (

Herzogenrath, W. & Kreul, A. eds. (2002) Sounds of the Inner Eye (John Cage, Morris Graves & Mark Tobey), Tacoma, USA: Museum of Glass: International Center for Contemporary Art

Kerouac, J. (1999) Some of the Dharma, New York & London: Penguin [Kerouac’s jumbled (but interesting) notes & thoughts on Buddhism – a ‘Beat’ perspective]

Loori, J.D. ed. (2002) The Art of Just Sitting: essential writings on the Zen practice of shikantaza, Boston, USA: Wisdom Publications

McEvilley, T. (1999) Sculpture in the Age of Doubt, New York: Allworth Press/School of Visual Art

McEvilley, T. (2003) The Art of Dove Bradshaw: Nature, Change & Indeterminacy, New Jersey, USA: Mark Batty Publisher

Merton, T. (1968) Zen and the Birds of Appetite, New York: New Directions

O’Connor, M. (2002) Where the World Does Not Follow: Buddhist China in Picture and Poem, Boston, USA: Wisdom Publications [translations of T’ang Dynasty poetry with photos of contemporary Chinese landscape & hermitages]

Pine, R. & O’Connor, M. eds. (1998) The Clouds Should Know Me By Now: Buddhist Poet Monks of China, Boston, USA: Wisdom Publications

Rawson, P. (1973) Tantra: The Indian Cult of Ecstasy, London: Thames & Hudson

Reps, P. (no date) Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, London: Doubleday Anchor

Seo, A.Y. with Addiss, S. (2000) The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen, Boston & London: Shambhala

Suzuki, D.T. (1970) Zen and Japanese Culture, Princeton, USA: Bollingen

Suzuki, D.T. (1971) Sengai: The Zen Master, London: Faber & Faber

Suzuki, S. (1970) Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind: Informal talks on Zen meditation and practice, New York & Tokyo: Weatherhill

Trungpa, C. (1976) The Myth of Freedom, Boston & London: Shambhala

Watts, A. (1989) The Way of Zen, New York: Vintage Books

Yokoi, Y. (1976) Zen Master Dogen: An Introduction with SelectedWritings, New York & Tokyo: Weatherhill

Websites

Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Buddhist Philosophy: http://www.rep.routledge.com/article-links/F001

Zen Philosophy: http://www.erraticimpact.com/~ancient/html/zen.htm

John Danvers March 2006