This illustrated talk titled, Creative awakening: Buddhism, art & everyday life, was given at the first Creative Awakening seminar, Ordinary or extraordinary living, Institute of Oriental Philosophy, Taplow Court, Maidenhead, UK. July 2010.

“Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; ….”

– from Pied Beauty (1877) by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Create v. 1.Bring into existence,

Give rise to; originate; design. 2.

Constitute, invest (person) with

rank. 3. (slang) Make a fuss.

(Coulson, Carr, et al 1980)

Creative awakening: Buddhism, art and everyday life

This presentation is a revised and extended version of the talk I gave at last year’s symposium. It is in two parts: in Part I I’ll explore ideas about how Buddhism, art and poetry can initiate and reflect a creative transformation of everyday life; in Part II I’ll offer some examples of creativity in action, particularly within the fields of art and poetry – including a few examples of my own work.

PART I ideas & issues

There is nothing special about creativity. Creativity is unavoidable, as unavoidable as breathing or sensing.

Each moment of consciousness is a creative moment, a manifestation of the infinite creativity of living and being. What artist’s do is only one of the infinite forms of creativity, a practice amongst countless creative practices – and these practices range from raising a child to running a business, gardening to plumbing, testing out a theory in a laboratory to sweeping the backyard, painting a wall to painting a portrait, writing a letter to writing a poem…. these are all manifestations of creative thinking and doing within the human realm.

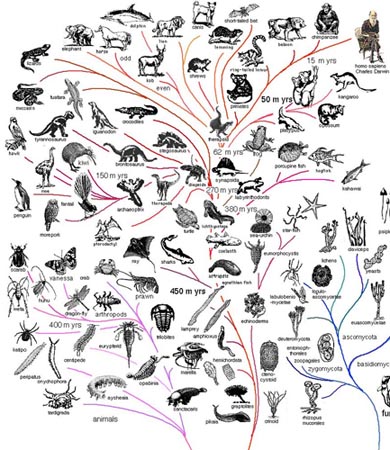

And on what grounds are we not to include the creativity of other species and natural forms. The blackbird singing endless melodic variations from his perch on the crab apple tree, the bees at work in and around the hive, ants ‘milking’ greenfly for their honeydew, chimpanzees sucking termites from the end of a stick they’ve probed into a mound – they’re all exercising powers of invention and adaptability. And what about the less obvious creative practices of clouds, endlessly performing subtle or dramatic cloud dances, or the slow ponderous music of mountain erosion or the pizzicato mutterings of mountain streams, or the stately, centuries long, growth of lichen on a Dartmoor boulder. Are there any boundaries between patterns of growth and decay in the natural world and the patterns of creative intelligence manifested in the growth of human imaginative constructs? I suspect there are no clear-cut distinctions to be made, unless we consider creativity to be defined by purposeful self-consciousness – in which case the zone of creative practice shrinks to a narrow and greatly-diminished sphere of activity.

*

We use the term creativity to refer to many different qualities and doings. It is often used to denote distinctive ways of being, thinking and making that demonstrate flexibility, innovation, inventiveness and the confounding of expectations and assumptions. Intuition, improvisation and non-linear ways of thinking are often emphasized, as are, experiment, trying-things-out, making a mess, working productively with high levels of disorder, uncertainty & indeterminacy. Elements of chance/serendipity are often essential – both in the creative process and in the products of creativity. And there’s often an element of spontaneity and of being surprised by what emerges. A sense of something unexpected, not predetermined.

From a Buddhist perspective creativity can be enhanced by the development of an open non-discriminatory mode of awareness – ‘mindfulness’ – a disinterested attention to all that arises – a non-centred awareness. In this way the creative stream of human being can flow unimpeded by the desires and demands of the deluded self.

Historical Detour

There is a widespread belief that creativity is associated with specialness, creativity as a distinctive characteristic of a few individuals – artistic and poetic ‘geniuses’ – whose actions and utterances are seen as being of a different (and superior) order to that of ordinary folk. Vasari paved the way for this break between the creative domain and the domain of the rest of us, when he began to write of Renaissance artists as eccentric individuals with special and unusual gifts. He saw this as evidence of human beings exhibiting God-like powers. Michelangelo becomes ‘the divine Michelangelo’. Evidence of divine intervention, of creativity as a ‘gift’ bestowed on a few rather than as an innate attribute of all, becomes part of the cultural sediment of the 19th Century and is canonised in 20th Century Modernism.

In this account creativity becomes the prerogative of artists, composers, poets and, occasionally, distinguished ‘men of science’. Blake’s image of Isaac Newton executing the geometry of God on an earthly surface embodies this view. Leonardo becomes the epitome of polymathic creativity, and Picasso is accorded the status of a demi-god – the icon of masculine virility and creative energy. The patriarchical power-base at the centre of this view is obvious. As is the rhetoric of fertility: ‘giving birth to ideas and images’; artworks as the ‘offspring or children’ of male artists; ‘fecundity of ideas’; etc. – all assuming an association between cultural production and biological reproduction, or, alternatively, male envy, fear or arrogance enshrined in the robust exercising of creative power.

However this view of creativity can be contrasted with the ideas of artists like John Cage, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, and philosophical thinkers like Ruskin, Merleau-Ponty, Howard Gardner and John Dewey, as well as many proponents of Buddhist thought and practice. In all of these sources we encounter a view of creativity as an integral part of our make-up as human beings. Creative thought and action are characteristic of our being in the world, dynamic attributes of our perceptual and conceptual systems. This poses a democratised challenge to the other elitist and restrictive view.

The Romantic/Modernist tradition considers creativity as both unteachable and as the genetic endowment of a few individuals: some people are creative, others aren’t – you’ve either got the ‘gift’ or you haven’t. On the other hand the counter-tradition I’ve described sees creativity as a fundamental capacity or potential of everyone – something that can be encouraged and nurtured and learned. Indeed learning itself can be seen as quintessentially creative.

Identity, Perception and Enlightenment

The French philosopher, Merleau-Ponty, argues that perception is itself a creative process by which we encounter, handle and make sense of the world of things and other beings. Perceiving the most insignificant object, involves a complex and creative encounter with otherness. We are knowing bodies implicated in the world, not separate from it.

Merleau-Ponty argues that creativity also builds and affirms a sense of identity, well-being and aliveness – what he calls ‘self-constitution’ – the making of who we are in each of our thoughts, actions and interactions with others and the world. Buddhist practice adds to, or subtracts from, this idea, the realisation (sudden or slow) that the ‘self’ is, in a sense, a fiction, a social construction, without any fixed or unitary essence. Recognising that we need not be defined and confined by an apparently enduring self, we can learn to let go, to change, to move from state to state, to be creative and to creatively be! By shifting our frame of reference we realise that the self is a ceaseless creative dance of embodied mind, constantly unfolding into new possibilities and potentialities. Through disciplined learning practices we can come to realise that the self is a dynamic creative process rather than a fixed entity.

These thoughts on selfhood can lead us to question the notion that we ‘have’ ideas. What is it to have an idea? Should it be the other way around – are we ‘had’ by ideas? Do we inhabit ideas, or are we inhabited by them? And who is it who ‘has’ the idea?

An idea arises as a moment of consciousness. The more we relax our hold on the linguistic or conceptualising self the more likely it is that ideas will arise out of the flux of interactions deep in the neurological system. Being in possessive mode in relation to ideas can be counter-productive. In a sense the less we try to ‘have’ ideas the more likely it is that they will arise. Getting our “selves” out of the picture may unlock the flow of creative neurological activity.

Experiential evidence from the sciences and the arts points to the effectiveness of ‘letting go’, even of ‘giving up’, allowing the intuitive, pre-linguistic processes to run ‘underground’ in the mind – at the margins of consciousness rather than at the centre of attention. In these conditions ideas often emerge in ‘Eureka’- mode! The Daoist phrase, wu-wei, ‘doing by not-doing’ seems appropriate – letting things happen of their own accord.

*

Meister Eckhart suggests that: ‘Art is an act of attention, not of will’. (often quoted by John Cage).

*

The seventeenth –century Rinzai Zen master, Bankei, (1622-93, also known as Kokushi) turns the popular notion of creativity on its head. He centres his teaching on what had been for centuries a key Buddhist term in Japan, Fu-sho, ‘the Unborn’, or Buddha-mind or Buddha-nature: that which is ‘intrinsic, original and uncreated’. (Haskel 1989: xxx) Bankei tells us that to be truly alive we need only recognise with all of our being that we are truly alive. The state of enlightenment, liberation or peace that human beings so frantically crave, is only to be realised by letting-go of the craving – which is built on illusion and mis-understanding. Similarly creativity, which is a manifestation of being truly alive, is not something that needs to be learnt or added to our being, rather it is a way of being that is most immediate and ready-at-hand, often realised by unlearning, unknowing, letting-go. Paradoxically, the process of realising by letting-go may require a very systematic discipline: the discipline of the koan, of Madhyamika dialectics, of ascetic routines and highly-organised periods of meditation – or the discipline of drawing a stone over and over again in order to see the stone as if for the first time – what Lawrence Weschler (1982) refers to with the phrase, ‘seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees’.

*

While creativity is usually lauded as ‘a good thing’, a quality always to be nurtured, it is important to keep in mind that creativity is not ethically neutral, let alone universally ‘good’. Sadly, human beings are as creative in the arts of war, cruelty and repression as they are in the arts of peace, care, tolerance and liberation. Creativity can be a force for good, a way to, and a manifestation of, enlightenment and liberation, but it can also be a force for domination, selfishness and exploitation. The way in which creativity is manifested and exercised defines its moral value, though paradoxically, as already mentioned, there is a kind of purposelessness or playfulness that seems integral to creativity.

The highest we can aspire to is the ordinary, the everyday, the humdrum – the art, or creative practice, of living. Attending, without clinging, to the stream of everyday experiences is a profound creative activity. Sawaki Roshi points out: ‘Everyday life has rainy days, windy days, and stormy days. So you can’t always be happy. It’s the same with zazen.’ (Uchiyama 1990: 52) Uchiyama adds that zazen is at heart ‘the practice of continuous awareness in the midst of delusion, without attachment to delusion or enlightenment.’ (ibid) In a similar vein Georges Dreyfus suggests, the everyday sound of two hands clapping may, in the end, be more important (and creative) than the rare sound of one hand clapping. (Dreyfus 2003)

Speaking very much in the tradition of Dogen and Bankei, Sawaki Roshi de-mythologizes and debunks the notion that satori or enlightenment are extraordinary or special attainments. At one point he goes so far as to say: ‘there is no way to fail in becoming a Buddha […..] The night train carries you along even when you are sleeping.’ (ibid: 54) He suggests that however we may clothe satori or enlightenment or Buddha Mind in special properties, there is in actuality nothing special about realising Buddha-nature – it is to be just as we are, no less and no more. The view of Buddha Mind as special is delusive in that it depends on attachment to the idea of specialness, it is to sit in meditation in order to become special (enlightened). It is to sit, polishing the tile of the self in the hope that it will become a mirror of enlightenment – but, as Nangaku [in Chinese, Nan-yüeh] (see Watts 1989: 96-97) and Dogen [in the Fukanzazengi] argue, it never does. Sawaki’s gentle critique of the tendency to mythologize or Romanticise Buddha Mind, can be applied to the tendency to Romanticise creative practice in relation to the arts – to diminish creativity by associating it only with genius. Paradoxically, as Dogen points out, if we polish the tile for its own sake, with no thought of reward, we may well realise Buddha Mind. (see Harmless 2007: 208)

Another aspect of creativity that is often neglected is the ability to make connections. We often think of creativity in terms of originality, making something out of nothing. But of course, all that comes out of nothing, is nothing. A pile of zeros is still zero. We always need material out of which to make something, whether it’s paint, bricks, flour or thought. Often creativity involves connecting something to something else, in a new or surprising way. Making connections, or noticing connections, is itself a creative act, and to notice connections is to be connected, to experience the interrelationship and interdependence of all that exists. The feeling of interconnectedness is also often accompanied by a feeling of compassion.

Sawaki Roshi, writes: ‘Zazen is the way through which you can connect with the whole universe.’ (in Uchiyama 1990: 80) Connecting to the universe involves setting aside the conditional or discriminating self to see things as they are in their infinite inter-dependence – this is to be free, to realise natural wisdom – to be wholly here. According to Sawaki when we realise true selfhood in all its transparency ‘there is no gap between the true self and all sentient beings’. (ibid: 20) And as there is no gap between beings, all beings are integral to ‘my’ being, a facet of the transparent or permeable self. As Uchiyama puts it:

everything I encounter here and now is a part of my life, I shouldn’t treat anything [or anyone, or any being] roughly. I should take care of everything wholeheartedly. I practice in this way. Everything I encounter is my life. (ibid: 124)

‘Everyday mind is the way’

Sekkei Harada makes reference to the famous koan in which: ‘Joshu asked his master, Nansen, “What is the Way?”’ – that is, ‘what is the Way of the Buddha’. Nansen replied, ‘Everyday mind is the Way’. (Harada 1998: 60)

Harada suggests that: ‘The words “everyday mind” express the condition of our lives free of our own ideas and opinions. Washing one’s face, brushing one’s teeth, talking, taking meals, working – all these activities [can] take place before thought’. (ibid: 164) That is, before we weave our chattering mind around them – adding layers of commentary and feeling to the activities themselves. Everyday actions are an actualisation of Buddha Mind if we don’t cling to them or add unnecessary layers of hopes, intentions, worries and expectations to them.

This accords with Dogen’s emphasis in the ‘Genjokoan’, on the activities of daily life – full of ups and downs, routines and seeming mundanity – as a continuation of the formal koans encountered in the temple context. For Dogen there are countless ways in which we can realise our Buddha-nature and countless modes of expression and communication through which we can manifest Buddha-mind – these range from verbal teachings and stories to the way in which we do things (for instance, walking, sitting, cooking), even the way in which we stand in a room. Indeed, Dogen shares with Jacob Boehme, a belief that the world and everything in it is a manifestation of cosmic creativity, an expression of what Dogen calls Buddha-mind or Buddha-nature, and Boehme calls God or Ungrund. (see Kim 2010)

*

One of the many difficulties of the apparently simple act of zazen, is to be aware of the endless stream of perceptions, thoughts and feelings, without becoming attached to any one of them – attending to the stream but not grasping at the fishes in it. This is reminiscent of the methods of ancient Greek sceptics who argued that we should not become entangled in the divisive web of language which tends to pin down or define what is intangible and indefinable. The sceptics thought that as nothing could be said to have a fixed, independent or absolute existence, including human ideas and opinions, it was best to suspend judgement and belief, and not to become attached to either side of an argument. Similarly we could describe zazen as sitting in non-attached attention, being aware of the endless creative play of opposites and possibilities, without taking sides.

*

Creativity is a process, a being-at-home with what occurs from moment to moment, being alive to the potential out of which all events and forms arise – a playfulness in the way we engage with ideas and life. It is also a state of not grasping at what passes, not standing in the way of, or trying to hang on to, the flux of life – creativity is both ‘skilful means’ and awakening to the way things are.

PART II a few examples of creativity in action

Vernacular Creativity

We are surrounded by examples of human creativity in daily life. From the endless creativity of gardeners and householders who raise crops, transform their urban patch of ground, customise doors and house-fronts, to the high-quality graffiti produced by individuals, often with no visual training. Skateboarding is sometimes done with exuberance, skill and high levels of inventiveness. At village fairs homemade cakes are made and decorated with artistry. Every day we pass in the street people who dress in creative ways, lending surprise and beauty to the morning walk to work. We pass enigmatic and thought-provoking signs and phrases that give us pause for thought and laughter. Street entertainers offer us wonderful manifestations of creative movement, music, magic and living-sculpture stillness. A garden shed is lavished with so much raw untutored artistry that we have to return for a second and third look. Because we are surrounded by the vernacular arts and by domestic inventiveness we can easily forget to recognise how creative people are in their homes and workplaces. Without any formal training many, if not most, people have a gift for some kind of creative practice: verbal, manual, technical or social. While some people exercise their creativity in provocative and possibly ‘anti-social’ ways, others use endlessly inventive ways of de-fusing tension, bringing people together or bringing about social, cultural or political change.

John Cage

The composer, artist and thinker John Cage, recounted how when he was young he wanted to change the world. As he came to realise he wouldn’t be able to do this he became somewhat frustrated and despondent, until he realised that although he couldn’t change the world he could change the way he viewed the world – he could change himself and how he thought and acted. This insight lead first to greater harmony and a sense of well-being, and also to a life of endless creativity in which in a curious way he did ‘change the world’ – or at least that part of the world we call music and art.

He spent his career encouraging us to open our ears to the soundworld that surrounds us all the time, and to open our minds to indeterminacy, to chance events and the endless surprising routine of everyday life – which, once we get our preconceptions and thinking habits out of the way, can be a source of endless delight and wonder. This is Cage’s view of the creative life.

Here are some fragments of his writings re-orchestrated by me to give a flavour of his thought:

Our poetry now is the realisation that we possess nothing

Out of a hat comes revelation & a pianist. On the way, she said she would play slowly. On the way she would play slowly. She said on the way she would play, play slowly. Everything, he said, is repetition. Slowly she would play. She would say playing slowly she hoped to avoid making mistakes, but there are no mistakes – only sounds, intended & unintended. A glass of brandy

There are already so many sounds to listen to. Why then do we need to make music?

We must work at looking with no judgement, nothing to say. All art has the signature of anonymity

Art is a job that will keep us in a state of not knowing the answers

Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread became famous for a project called House, made in 1994 in the East End of London. At the heart of Whiteread’s work is a simple but creative inversion that has complex implications: the transformation of an ‘empty’ space into a solid object. So Ghost, 1990, is a cast in plaster on a steel frame of the inside of a room with fireplace, skirting board, doors and windows. The ‘space’, air and emptiness of the room becomes a pale, opaque, solid object. Inside becomes outside. Negative becomes positive. Absence becomes presence.

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)

The American poet, William Carlos Williams, was a family doctor in Patterson, New Jersey. His poetry combines precise, almost forensic, observations with the rhythms and distinctive phraseology of everyday speech. Some of his works are very short, distilling observations and reflections into carefully crafted poems of great resonance. Here’s one, entitled Silence:

Under a low sky –

this quiet morning

of red and

yellow leaves –

a bird disturbs

no more than one twig

of the green leaved

peach tree

And another poem entitled, The Hurricane:

The tree lay down

on the garage roof

and stretched, you

have your heaven,

it said, go to it.

(Williams, 1965)

ee cummings (1894-1962)

Here’s a poem by another American poet, e.e.cummings, demonstrating both his distinctive perspective on life and nature, and his creative use of verbal materials:

when god decided to invent

everything he took one

breath bigger than a circustent

and everything began

when man determined to destroy

himself he picked the was

of shall and finding only why

smashed it into because

Daniel Spoerri

Since the late 1950s, the French artist Daniel Spoerri has been making art involving the activity of eating and exhibiting the remains of meals. Table-tops with plates and cutlery, left as they are at the end of a meal, are preserved as stilled-lives – an unusual continuation of a long tradition of European still-life painting. Spoerri has also started and run three restaurants as eat art actions.

Marina Abramovic

Marina Abramovic has been working as an artist for over forty years. She has produced photographs, videos, installation-works and numerous performances, many of which involve extended acts of attention. These are sometimes related to very humdrum domestic situations – as in this recent work in which she peels onions.

On other occasions the acts are more extreme, often involving a relationship with someone else – for instance in a work from 1977, in which visitors to the gallery had to squeeze between Abramovic and her collaborator to get from room to room, or in this piece of heightened concentration (bow & arrow):

Poetry, listening, praying

The Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie suggests that poets are listeners, carefully attending to the goings-on in the world, including the world of the mind:

When we were young, we were told that poetry is about voice […] but the older I get I think […] it’s about listening and the art of listening, listening with attention. I don’t just mean with the ear; bringing the quality of attention to the world. The writers I like best are those who attend. (in Scott 2005: 23)

Jamie connects the act of attending, of listening, to the act of praying. When her husband was seriously ill with pneumonia, a friend asked if she had prayed, to which she replied that she hadn’t in any formal sense. But, she went on,

I had noticed […] the cobwebs and the shoaling light and the way the doctor listened and the flecked tweed of her skirt… Isn’t that a kind of prayer? The care and maintenance of the web of our noticing, the paying heed? (ibid)

Ken Friedman

As a member of the Fluxus group of artists, Ken Friedman has spent almost his whole career transforming life into art. Influenced by John Cage and others, he has been writing “scores” for actions. These can be seen as invitations to everyone to participate in acts of creative transformation – they can also be seen as part of Friedman’s practice of compassion, like an artistic Bodhisattva opening up the possibility of enlightenment to anyone who comes across his scores.

Dove Bradshaw

Dove Bradshaw’s Indeterminacy series, consists, like many of her works, of objects and materials that undergo chemical change over time. One work from the series consists of a small lump of pyrite rock placed on a much larger piece of Vermont marble. Placed out of doors, accessible to rain, the pyrite leaches chemical stains that spread in an indeterminate fashion over the marble. The process continues as long as the rocks are exposed to moisture. Bradshaw notes the date on which the work is activated, not made, and she photographs each work every few years to record the changing forms. We can watch the slow transformation of materials and recognise that just as there are no fixed boundaries to hard objects there are no fixed essences to the human self. The self is a fluid porous boundless continuum. Eventually the rocks will erode & wash away – as we all do!

Tim Knowles

Over the past decade, the English artist, Tim Knowles, has been exploring indeterminacy in artmaking. In one series of works he has made simple constructions to record the movements of branches and leaves on trees. Drawings are made (in graphite or ink on paper) by attaching a drawing implement to the ends of branches and allowing them to leave traces of their movements. These drawings are often mounted alongside photographs of the site of making. Knowles deliberately aims to remove his own authorial control from the drawing – in a sense he acts as an agent for the tree, enabling the tree to make a direct indexical sign of its creative presence in the world.

Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono offers her own quirky mix of disturbance, insubordination and wry humour. She plays with ideas of seriousness, deflating expectations and gently nudging us to see things differently. Her works also enact a playful feminist critique of macho-modernist conventions in art.

Yoko Ono Fly 1996

Yoko Ono Fly 1996

Although poets and artists are seen by many as having special gifts or insights, much of the time it is only that they attend to what is around them in a non-discriminatory way, they are mindful. It is in how and what they notice, and how they share their perceptions with others, that their creativity is demonstrated. They often notice and value what is unnoticed and unvalued by others. In this way the ordinary becomes extraordinary and the mundane takes on a vivid hue.

Sometimes it’s enough to see something on the way to work:

on the road to

the station a one-eyed

seagull meets a

man with a large

head

[12.11.07]

Or to notice the whole of a season embodied in one small incident:

summer on the blue rocks

a fly scratches

*

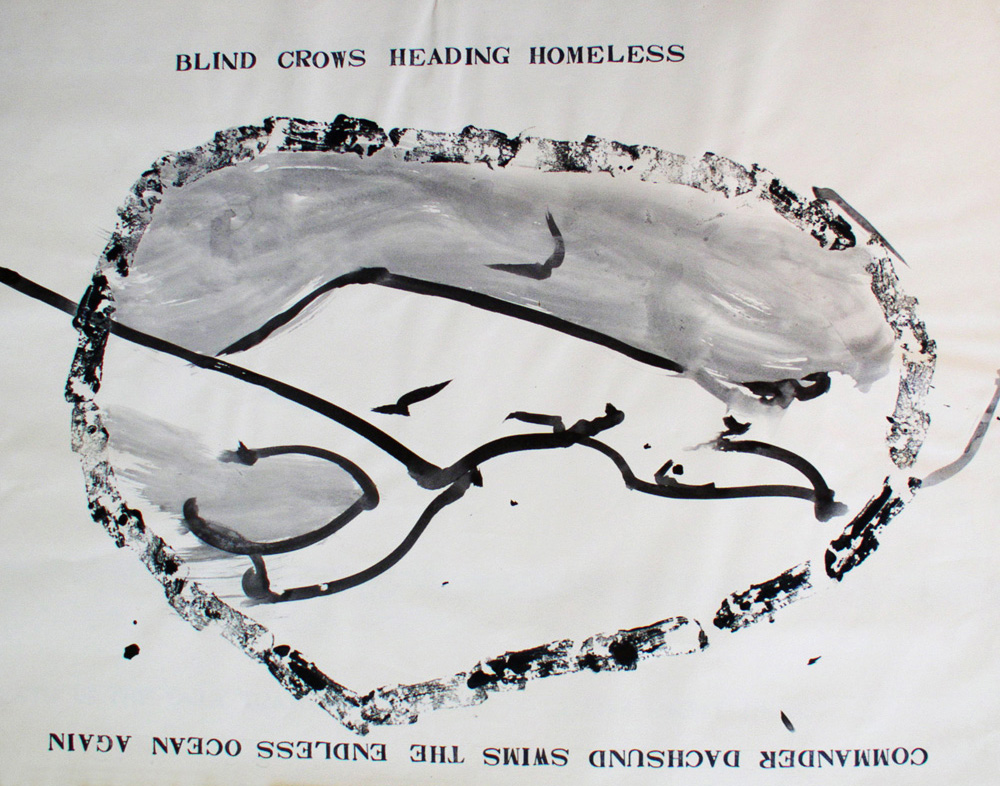

Here is an invertible drawing of mine: Commander Dachsund……

And here it is again: Blind Crows…..

*

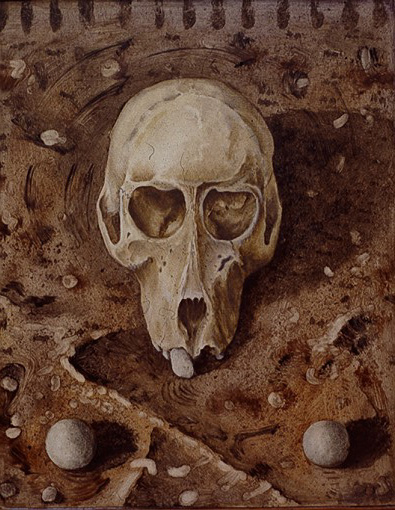

For ten years or so I made still-life paintings. While these can be seen as fairly orthodox artworks in a realist tradition, for me the paintings were a trace or distillation of long hours and days of carefully attention – observing the humdrum objects in front of me – realising they were neither humdrum nor really objects – they are fields of attention or perception, pulsating with the rhythm of my shifting viewpoint, the dynamics of neuronal activity in my brain and the pulse of sub-atomic energies connecting everything.

Baboon Skull Study Nov 1990

Baboon Skull Study Nov 1990

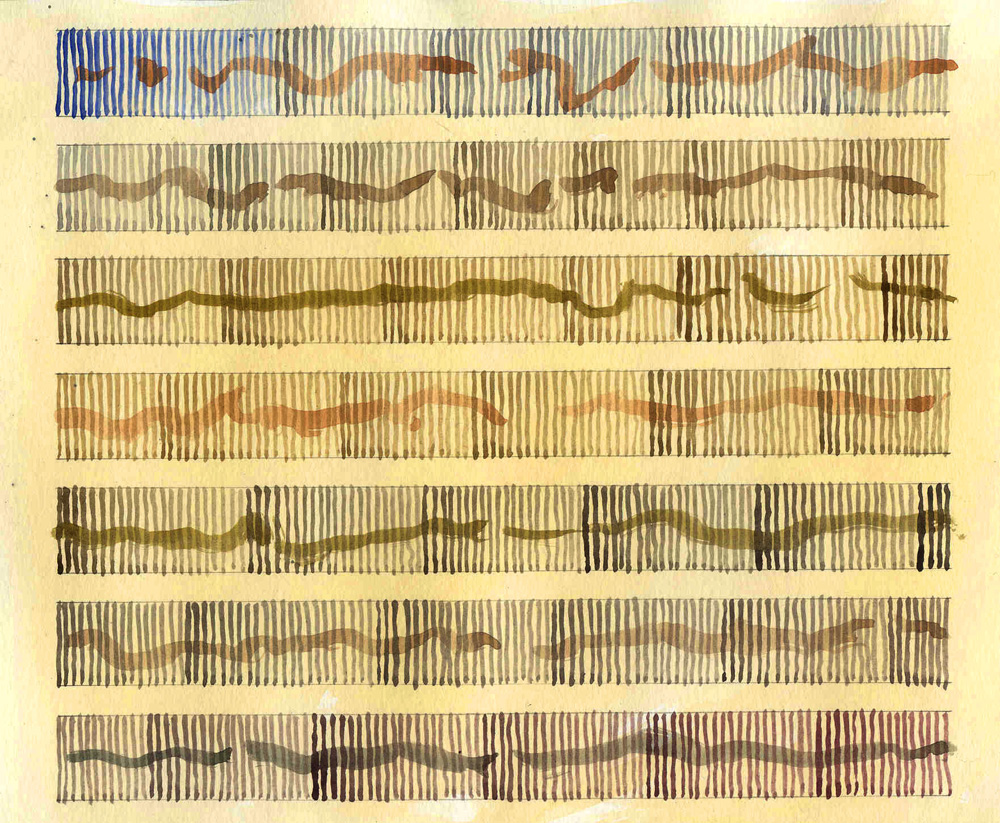

Here’s an example of art WORK as visual meditation – repetition – literally marking time:

*

To put everything I’ve said so far in another form:

Fresh turn again to ideas familiar strange. Immeasurable

dance of action being chance surprise. Standing thinking,

every human chaos. Sewing shut to open smooth round

stone. Illogical leap to incomplete, as small disturbed bird

on twig in dappled mind all stippled calls to trout. Whatever

turns to bulls-eye works. So to make a mess, try this, try that,

give up, go home. Turn again to dance with chance unfolding

rhetoric of surprise. Full circle to chase wild goose. Lucid

elusive river-run. Awakening to each fish that flicks its tail,

one fish after another after another – sudden light

hitting dappled dark, river-stones turned to silver eels

or, in Issa’s (1763-1827) words:

simply trust

do not the petals flutter down,

just like that

(in Blyth 1949: 207)

References

Blyth, R.H. 1949. Haiku Volume 1: Eastern Culture, Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press.

Coulson, J., Carr, C.T., et al. 1980. The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary, London: Book Club Associates.

Dreyfus, Georges, B.J. 2003. The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Gardner, W.H. 1964. Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Selection of his Poems and Prose. London: Penguin Books.

Gibson, J. J. 1966. The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Griffin, Susan. 1982. Made from this Earth: Selections from her Writing, 1967-1982, London: The Women’s Press.

Harada, Sekkei. 1998. The Essence of Zen: Dharma Talks Given in Europe and America, Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Harmless, William. 2007. Mystics, New York: Oxford University Press.

Haskel, Peter. 1989. Bankei Zen: Translations from the Record of Bankei, New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Kim Hee-Jin. 2010. Dōtoku – Expression. On line at http://earlywomenmasters.net/shobogenzo/d/dotoku/dotoku_kim.html (consulted 31.03.2010).

Uchiyama, Kôshô. 1990. The Zen Teaching of ‘Homeless’ Kôdô, Kyoto: Kyoto Sôtô-Zen Center.

Weschler, Lawrence. 1982. Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Williams, W.C. 1965. The Collected Poems, MacGibbon & Kee.