This paper, entitled, Stuttering at the Owl: poetic displacements & emancipatory learning, was given at the Discourse Power Resistance conference, New Directions, New Moves, University of Plymouth, UK. April 2003. It is also published as a chapter in Satterthwaite, Atkinson & Martin, eds. 2004. Educational Counter-cultures: Confrontations, Images, Vision. Trentham Books, p.165-182.

Introduction

In this presentation I hope to show how the radical ‘displacements & inventions’ of certain kinds of poetic practices, can, and do, act as an alternative to the dominant techno-rationalist discourses of many of our contemporary social & cultural institutions. Examples of non-linear writing, picturing and object-making will be presented as strategies of cultural resistance. I’ll also briefly explore the implications of these practices & modes of being, knowing and doing, for the development of a more ludic pedagogy in which participation, indeterminacy and a transformative approach to learning are affirmed.

As an artist-learner-teacher working within a Buddhist-pragmatist framework I am attempting to disinter and reconstruct an emancipatory project for learning and teaching through art practice. This could also be considered as aiming to develop and enact a radical pedagogy grounded in individual and collective transformation, critical scepticism and experiential engagement. (Danvers, 2003: 47-57)

Atkinson (2002) has developed the idea of ‘pedagogised identities’ to describe the ways in which different learning and teaching contexts and normalising discourses (eg assessment regimes or developmental theories) produce different kinds of identity in learners and teachers. Within art education he argues that ‘these discourses produce students’ abilities in art practice’ – a challenge to the view that these abilities are ‘natural endowments’ awaiting discovery or deployment. Recognising the power inherent in the vocabulary, syntax, register and mode of articulation used in a particular institutional discourse, also enables us to see the potential to disrupt or resist that power by modifying the syntax or destabilising the terms and structures of signification. To some extent at least we can reclaim control of our self-construction and cultural identity by developing a new counter-discourse and establishing affiliations with extant traditions of counter-discourse. Modern, postmodern, tribal and other radical poetries and arts practices provide examples of viable counter-discourses, both verbal, visual, material and spatial, which are explored in this chapter.

*

The text is organised in a series of discrete sections that illuminate different aspects of the field of enquiry. Each section is both freestanding and in some way related to the others. The images are included to provide a visual enactment or complementary picturing of some of the ideas under discussion. The fragmentation and discontinuity within the text are presented as forms of resistance to normalising discourses of knowing, learning and being. The sequencing of text fragments and images is intended to surprise, to disrupt expectations and to encourage associative thinking on the part of the reader – an invitation to participate in the construction of meaning and interpretation.

Discontinuities and resistance

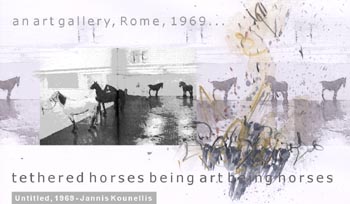

I open my book to an image of horses stabled in an art gallery. It is Rome, 1969. Jannis Kounellis is exhibiting the horses as art or as a question mark in the face of art. The work is untitled. The horses move, make horse noises and fill the air with horse smells. Buckets and a broom stand in the corner.

Despite their location the horses resist categorisation as art. They pull at the ropes tethering them to the wall. The glare of gallery lights exposes every vein and mark on their skin.

We seek some resolution of our uncertainty. Why are they here? How are we expected to view them? What idea is the artist enacting? What does this spectacle mean?

There is nothing to help us. No explanation, title or commentary. All we have are eleven horses – being horses – tethered in a large, brightly lit, space.

*

In Samuel Beckett’s novel, Watt, the protagonist Watt, watches and listens to the piano tuners, Mr Gall Senior and Junior:

The mice have returned, he said.

The elder said nothing. Watt wondered if he had heard.

Nine dampers remain, said the younger, and an equal number of hammers.

Not corresponding, I hope, said the elder.

In one case, said the younger.

The elder had nothing to say to this.

The strings are in flitters, said the younger.

The elder had nothing to say to this either.

The piano is doomed, in my opinion, said the younger.

The piano tuner also, said the elder.

The pianist also, said the younger.

This was perhaps the principal incident of Watt’s early days in Mr. Knott’s house.

*

In October 1940, having left Paris for Vichy, Samuel Beckett joined the French Resistance movement. In August and September 1942 he was on the run from the Gestapo. According to Marjorie Perloff, during these two months he was obliged to hide in many odd places, including:

…the crawl space beneath the attic in Nathalie Sarraute’s house (where Beckett was shut up for ten days in this suffocating space, together with Sarraute’s aged and ill father); he spent a terrifying night in a tall tree in the woods… while below him the Germans made periodic patrols with dogs and guns; and later, he and Suzanne hid in a series of barns, sheds, and haystacks on the way to the south, walking only at night when they were relatively safe. When they finally arrived at the village of Rousillon… they were in a state of physical and mental exhaustion. (Perloff 1996:125)

Perloff makes a very persuasive argument for linking Beckett’s involvement in the Resistance, and particularly the use of a complex ‘cut-out’ system used by his ‘Gloria’ cell to prevent infiltration, and the compositional structure of his novel Watt. The ‘cut-out’ system ensured that discrete fragments of information were passed on from person to person in such a way that only the person at the end of the chain could fit the fragments together and make sense of the whole. Watt was written by Beckett in short bursts during the five-year period from 1940-45, coinciding almost exactly with his Resistance experiences. The novel is full of discontinuities, non-sequiturs and uncertainties. In Perloff’s words: ‘Plot counts for very little, one event never logically leading to another and interruption (in the form of poems, songs, lists, and charts) occurring frequently.’ ‘No character, no plot, no symbols, where none intended’ – as Beckett famously put it. (Perloff 1996: 126)

Prior to the writing of Watt, in 1937, Beckett had noted:

It is indeed becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at things (or the Nothingness) behind it… Let us hope the time will come, thank God that in certain circles it has already come, when language is most efficiently used where it is being most efficiently misused.

Beckett strives to resist the formulaic structures of ‘official English’ – to usurp the power of the dominant discourse by disrupting the sound surface of the language. (Perloff 1996: 120-121) In relation to Beckett, Perloff argues, ‘The resistance to language… must be understood in terms of ‘the language of Resistance’.’ (Perloff 1996: 22)

*

In his song, Til I Die, Brian Wilson, the elderly Beach Boy, writes: ‘I’m a leaf on a windy day / Pretty soon I’ll be blown away.’

*

Wittgenstein, in his Notes on Logic, writes: ‘Distrust of grammar… is the first principle of philosophising. And, by extension, of poeticising.’ (Perloff 1996: 17) In the Philosophical Investigations, he resists imposing an artificial continuity on his own thinking and writing, even an organic linearity, because it would constrain his criss-crossing, disjunctive patterns of thought – what Perloff calls his ‘revisionary’ methods of composition. This process of sustained uncertainty and indeterminacy becomes a tacit benchmark of a new kind of philosophical practice, which involves both a critique and a revisioning of language through the use of anecdote, enigmatic utterance, associative imaging, seriousness and playfulness, assertion and counter-assertion. The need to destabilise, to jolt the reader out of his or her preconceptions and intellectual comforts becomes an important part of Wittgenstein’s philosophical project.

This description of philosophical method could also be used as a manifesto for learning and teaching. Embracing the equivocal indeterminacy of language as a given we can see learning and teaching as a discontinuous series of dialogue events, an exchange of conundrums, puzzles, uncertainties and ponderings, that liberate us moment by moment from the tyranny of ‘unthinking’ (to use e.e.cummings’ term), enabling us to resist in small ways the hegemonic structures of institutional discourses that demand a relatively supine acceptance. Cummings employs all manner of grammatical and typographic devices and displacements as a form of resistance to the normalising power of the conventional sentence. He prods us out of unthinking into linguistic attentiveness and engagement:

all ignorance toboggans into know

and trudges up to ignorance again:

…

one’s not half. It’s two are halves of one:

…

pity this busy monster,manunkind

(Cummings 1963: 65, 57, 56)

As Ingeborg Bachman puts it, there are times when one has to be

…against every metaphor, every sound, every rule for putting things together, against… the inspired arrival of words and images… suspicion is important… suspect the words, the language. (Perloff 1996: 151)

This suspicion helps us to resist the institutional construction of the subject – the technocratic determinacy that builds subject identities through conformity to dominant patterns of language, behaviour, desire and sublimation. The identification and deconstruction of these dominant patterns is central to a view of learning as a transformative and emancipatory project – enabling each of us to re-constitute our subjectivity in new ways, to reformulate ourselves in terms other than those we are given by context, habit, or the ‘official English’ of rule-making institutions and traditions.

*

On the other hand, confounding expectations should not become a new orthodoxy. Vermeer can be as liberating as Damien Hirst.

Unlearning, unknowing and letting go

What is it to know? Are learning and knowing synonymous? Is to learn to know, or to be with not-knowing – to be dynamically resigned to uncertainty and to an open-ended series of speculations? Unlearning is an important process within art education – a disciplined letting-go of habits of thought and practice. Unlearning, unknowing, letting go and wordlessness can be seen as modes of being and doing (or undoing) that contrast with, though dynamically related to, rational, acquisitive, worded and cognitive modes. Learning and unlearning involve destabilisation, transformation, change – processes of dissolving opacity, undoing knots – but only to move to the next knot, the next eddy in the flow. All we can do is exchange one conundrum for another in a process that is more akin to free association than logical progression or problem-solving.

*

Tristan Tzara – from The Approximate Man

I think of the heat that language weaves

– around its core the dream they call us by

(in Rothenburg and Joris 1995: 499)

*

Beckett told Tom Driver in a 1961 interview:

We cannot listen to a conversation for five minutes without being acutely aware of the confusion. It is all around us and our only chance now is to let it in. The only chance of renovation is to open our eyes and see the mess. It is not a mess you can make sense of. (in Perloff 1996: 133)

Beckett may have in mind a process of renovating our selves, reconstituting the subject. If renovation is to happen in educational contexts, if we are to reconstitute ourselves, we need to open our eyes, see the mess and let in the confusion!

*

Questions like, ‘What does it mean?’ may be irrelevant and inapplicable to many art practices and products, and to many events and situations in the (dis)course of life. The rising sun does not mean anything, nor does the Mona Lisa. Facts and artefacts do not provide predetermined meanings, instead they are the non-signifying context within which we temporarily rest to build the shelters which are our selves. We make these shelters of words, signs & gestures from which to engage our surroundings for a moment before we break camp, throw water on the fire and move on to make another shelter, and another.

The materials for our shelter-making are those that others also use. Protocols of usage can come to govern what we do and how we build, to the point that we begin to move into prefabricated structures and enact prefabricated lives. Somehow the exercise of poetic resistance and ‘suspicion’ enables us to make bespoke shelters of words, signs and gestures that are more like a tent or bivouac than a house, or more like clothing or a second skin. The temporariness of selfhood is permanent, even if we imagine it to be otherwise.

*

Out in the desert, a man lived in a hut. To him it was nothing special. He’d lived in many places. This was just another in a long line. Maybe they weren’t all as small as this, nor as temporary, but this was much like its predecessors. Four walls, a roof, a doorway (though no door). No windows. But light came in through the many holes and openings. Here it is. A space, refuge, shelter. Somewhere out of the sun and the wind.

Some say the tin shack accounted for his cryptic speech, his non-sequitorial grammar, the salmon leaps of his utterances. Others thought he’d brought these with him from a life of wandering – the disjointed travels echoed in his disjointed discourse. He moved from place to place, not in search of something, or running away from something, but somehow as a statement of being at home anywhere. He was always at home. Yet he was also both an immigrant and an émigré wherever he went.

*

Two lovely words: ‘dromomania’ – an abnormal, obsessive desire to roam; and ‘drapetomania’ – an uncontrollable desire to wander away from home.

*

Beckett’s Cast-offs:

once safely navigated life all over extinction ~ from the unuttered parenthesis the first cliche ~ yet art is a longer perspective ~ annihilation, dignified in its own way, is a stylistic change ~ he told me to disappear in vain ~ blown roses left in peace, humus mingled with the here dead set down shaft of dark in the Rue de Seine ~ back over the years, forty years of neglect intimate to us ~ and this was brevity, perhaps breathing or extinguishing, glimpsed for the first time only as it is going darting besieged by inexistence ~ a lengthy episode in many filaments ~ tenderly the needle stops midstitch

(Danvers 1999)

*

In May 1917, the dadaist poet and performer, Hugo Ball writes in his diary:

…in these phonetic poems we totally renounce the language that journalism has abused and corrupted. We must return to the innermost alchemy of the word; we must even give up the word too, to keep for poetry its last and holiest refuge… (Cobbing and Griffiths 1992)

Here’s an example of one of Ball’s phonetic poems, titled: Sea Horses & Flying Fish:

tressli bessli nebogen leila

flusch kata

ballubasch

zack hitti zopp

zack hitti zopp

hitti betzli betzli

prusch kata

ballubasch

fasch kitti bimm

zitti kitillabi billabi billabi

zikko di zakkobam

fisch kitti bisch

bumbalo bumbalo bumbalo bambo

zitti kitillabi

zack hitti zopp

(in Rothenberg and Joris 1995: 297)

*

Jerome Rothenberg proposes his ‘ethnopoetics’ as a ‘counter-language’ to the deadening cliches of official institutionalised languages. (Rothenberg 1994) He gathers examples of such a poetics in a number of anthologies that bring together poetries and songs from the oral traditions of native tribal peoples around the world, alongside radical modern and postmodern texts that disturb the smooth syntax and semantics of the dominant discourse. (see Rothenberg 1969, and Rothenberg and Joris 1995 and 1998) The anthology becomes a mode of cultural dialogue and a statement of cultural resistance to the beliefs, values and practices of technocratic and bureaucratic instrumentalism – providing alternative voices to the rhetoric of efficiency, accountability and other managerial orthodoxies. Rothenberg affirms the value of multiplicity and diversity, of polymorphous languages and identities – a plurality of being, knowing and doing – rather than the pursuit of enduring certainties and conformity, or of terms and phrases that offer solutions, or of vocabularies that aim to pin down, fix, define, judge or quantify.

Hybrids, hyphens and margins

These ideas can be linked to the work of the Chinese/Canadian poet, Fred Wah. In his poetry and poetics Wah explores the ‘hyphened position, a hybridised identity’. He writes:

The half-breed shares with the nomadic and diasporic, and the immigrant, the terms of displacement and marginalisation. Yet the hybrid, even in those relegated spaces of race and ethnicity, is never whole. It is the betweenness itself, however, that becomes interesting. (Wah 2002)

This notion of the ‘hyphened position’ can also be applied to any of us trying to survive existentially, poetically and ethically within a comforting but alienating technocratic culture. Many of us are marginalised, forced into a cultural nomadism in which we seek out voices and positions that articulate alternatives, enabling us, temporarily at least to feel kinship. Those voices and positions may belong to radical modern or postmodern artists and poets, tribal songmakers, scattered mythmakers and mythcritics, or passing individuals who light up the street and transform everyday experience.

Wah continues:

The discourses of other marginalized positions have always interested me as fodder for a resistance to being a fixture of colonization. Writers have to make choices about language and when you’re writing in the language of the colonizer any overt play against the grain can be generative. (Wah 2002)

Many of us have to write in the language of the colonizer within our professional roles, and many of us have to find ways of playing against the grain in order to regenerate and enliven ourselves.

Within learning and teaching we have to find ways to enable students to live and speak ‘against the grain’, to recognise their own hybridity and to establish kinship with others (however distant in time and space) who share a ‘hyphened position’ at the margins of the dominant technocracy.

Education as ‘open work’ – a multitude of stories

How can we, each in our different ways, resist the encroachment of narrowly-focused utilitarianism and determinism in the fields of learning and teaching? Working under the reductionist banners of ‘preparation for work’, ‘employability’, ‘accountability’, ‘learning outcomes’, ‘learning contracts’, etc, we lose sight of a more emancipatory and transformative view of education. We lose sight of the need to develop our citizens as human beings, alive to themselves, to each other and to the world in which we live.

In order to become more fully alive, to be open to experience and to reconstitute ourselves day-by-day we need to find ways in which our gifts, skills and aspirations can be identified, developed and exercised within a conceptual framework that is questioning, critical and analytical – yet attentive, celebratory and able to sing. We need to be able to distinguish between important and unimportant needs, and to separate out the strands of manipulation and coercion that all social institutions deploy. We need to embrace the discontinuities of life and the endless puzzles that engage us as learners, in order to teach in ways that are indeterminate and open – allowing those we teach to interpret, make meaning and demonstrate learning in surprising stories and inventive actions and forms.

Philosophical thinking as exemplified by Wittgenstein’s ‘distrust of grammar’, Bachmann’s ‘suspicion’ of the words, and Beckett’s tearing apart of the ‘official English’, has to be worked for at all ages and in all the contexts of learning – formal and informal. This kind of thinking can be related to Foucault’s archaeological methods of discourse analysis, Derrida’s deconstruction of the binary structures of inclusion and exclusion, and the pragmatist critiques of social and intellectual institutions articulated by Richard Rorty. Rorty argues that the socialising function of education needs to be counter-balanced, or even subverted, by an ‘individualizing’ function that involves ‘… a matter of inciting doubt and stimulating imagination’ in order to foster ‘self-creation’. (1999, p118) The ability to sniff out the convoluted, multi-layered, mycelia of power has to be matched by the capability of constructing alternative structures of signification – to disturb and revitalise the familiar patterns of discourse, with new songs, stories, actions and images.

*

Robert Smithson, in his 1966 essay, Sedimentation of the Mind, writes:

Words and rocks contain a language that follows a syntax of splits and ruptures. …This discomforting language of fragmentation offers no easy gestalt solution; the certainties of didactic discourse are hurled into the erosion of the poetic principle. (Flam 1996)

An open igloo made of metal struts and sheets of glass stands in a gallery space, with a bare-limbed branch protruding from the top. The artist, Mario Merz, calls it: Igloo with a Tree. The story-maker inside us begins to stir. We see it as a statement about the colonisation of tribal peoples, or the expropriation of vernacular architecture by late modernist European high art, or a witty juxtaposition of tree and arctic houseform. The ancient symbol of a tree of life points to some kind of resurrection of ethnicity in the face of global capitalism.

The structural simplicity of the shelter points to a post-industrial age of subsistence architecture in which we endlessly recycle materials. We shudder at the way the branch seems to be trying to escape the glass-toothed dome, a leafless dying gesture of resistance, memorial to a way of life no longer sustainable. We notice the glass reflects back at us our own image as coloniser – a consumer eager to find a new taste to stimulate our easily jaded palettes. And yet we can also see through the glass, through the domed form, taking in the rest of the room, seeing other spectators eating the art in the same hurried manner.

We voice all these stories and more. And none seems more true than another. There is no mono-meaning, no single content or point – only multiple stories woven around the spare arcs of metal, planes of glass and filigree of wood. There is also wordless wonder, perplexity or surprise, a mute engagement or silent encounter with the artwork. In the end it defies consumption, it is both meaningless and meaning-full, valueless and invaluable.

Umberto Eco (1989) provides us with some kind of academic legitimation for our varied interpretations – an open igloo a perfect exemplar of his ‘open work’. According to Eco the ‘open work’ constitutes ‘a field of open possibilities’ (p86) arising from ‘its susceptibility to countless different interpretations which do not impinge on its unadulterable specificity. Hence, every reception of a work of art is both an interpretation and a performance of it.’ (p4) Eco refers to Pousseur, who ‘observed that the poetics of the ‘open’ work tends to encourage “acts of conscious freedom” on the part of the performer and place him at the focal point of a network of limitless interrelationships…’. (p4)

Education, the processes of learning and teaching, can be seen as an ‘open work’ leading to unpredictable stories, meanings and changes of mind. In this view of education, learner and teacher are active participants in personal and collective acts of story-making, and learning is always indeterminate as to outcomes. Rather than consumers of education we are producers of learning – enacting or performing our learning within ‘a field of open possibilities’.

*

Tristan Tzara – from The Approximate Man:

what is this language whipping us we jump at lights

our nerves are whips held in the hands of time

& doubt comes with a single faded wing

screws into us & squeezes presses deep inside

like wrappers crumpled in an empty box

gifts of another age to swirls of bitter fish

(in Rothenberg and Joris 1995: 496)

The insubordination of words

Guy Debord reminds us that though words and images are ‘employed almost constantly, exploited full time for every sense and nonsense that can be squeezed out of them, they still remain in some sense fundamentally strange and foreign… We should also understand the phenomenon of the insubordination of words [and images], their desertion, their open resistance,’ (in Rothenberg and Joris 1998: 419) which is manifested in many forms of poetries, artefacts and performances. These forms displace the status quo and the given, in favour of the unexpected and subversive. I once heard the poet, Gary Snyder, in a radio interview, refer to this subversive quality in poetry as the ‘stuttering voice of revelation’.

*

This brings to mind Coleridge’s notebooks, fragmentary records of his myriad-mindedness, manifestations of the ‘flux and reflux of the mind in all its subtlest thoughts and feelings’. (in Perry 2002: vii) According to Perry ‘it was the Notebook, in its unplanned, unfolding, various existence, which allowed his multiform genius its natural outlet.’ (ibid: viii) Coleridge resisted the temptation, or pressure, to unify and synthesise his material, instead he aimed to be true to ‘his mind’s immense and multiple activity, in all its unmeeting extremes.’ (ibid)

*

Debord (in Rothenberg and Joris 1998: 419) points to the opposition between ‘informationism’ – the discourses of bureaucracy, officialdom and consumerism – and radical, transformational poetries, philosophies and arts – those kinds of poetry, philosophy and art that make us sit up and take notice, to pay attention to the architecture of signification, and to become open to changes of mind, revisions of self and subjecthood.

These fault lines can be extended into the terrain of education. ‘Informationism’ and managerial determinacy in Higher Education can be counteracted by emancipatory teaching strategies that foreground learning as a process of expanding critical and imaginative powers, an ‘open work’ in which we each develop a voice to sing the world into a better shape, or make objects and performances that revision life’s potential and actuality.

In economic, social and cultural spheres we face a kind of creeping totalitarianism that is already close to sweeping away dissent and diversity. Cultures of teaching and learning are reinforced by, and reinforce in their turn, the narrow-minded controlling impulse of government and big business – a powerful managerialism that values conformity to process and method above the development of aspiration, imagination, understanding and engagement. Passivity, resignation and a feeling that change is impossible are both symptomatic of alienation and disillusionment, and a necessary condition of particular kinds of political and economic structures. In the dialogues and encounters that lie at the heart of learning and teaching we can expose these structures, reclaim and revitalise alternative traditions, and open up new ways of thinking, articulating and acting.

*

A Verdi Chimney For Jannis

As Rimbaud said in a letter to Paul Demeny, 15 May 1871: every poet is a thief of fire

… all his life he wanted to paint among the ruins but time was against him ~ in a sense it is like being ~ mostly the weather is clear, then grey ~ it is like being a refugee, a little cloud ~ stabled horses are a sign ~ nomads are not tramps ~ it is like being on a ship, burning laurel at the beginning of time, broken sculpture in the sun, St John the Baptist, a white horse, a blackbird ~ old silence like a rose, a train, a border guard

everyone has a right to think, to be nervous, to abandon history ~ every word is a small oil lamp and provides just enough light

[text constructed from fragments of a Jannis Kounellis exhibition catalogue, Van Abbemuseum, Holland, 1981] (Danvers 1999)

*

In S/Z, Barthes writes about the ‘writerly text’ as being indeterminate in meaning, open to a plurality of readings, based as it is on the ‘infinity of languages.’ (1990: 5) Applying the practices of radical poets, artists, mythmakers and mythcritics, can become a vital part of an emancipatory approach to learning and teaching – a project in which we (teachers and learners) become active producers rather than passive consumers.

Coda

Coda

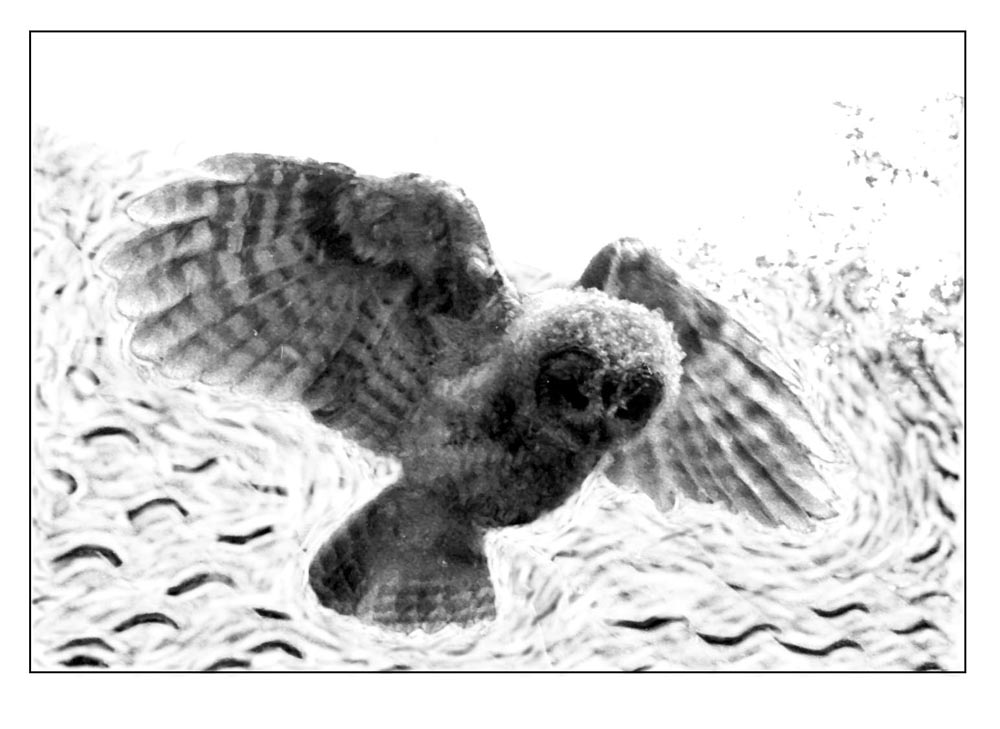

In his book The Spell of the Sensuous, Abrams (1997: 87-88) describes how the Cree peoples of North America believe that owls can cause stuttering and an incapacity to speak. Yet if they hear stuttering they are fascinated by it. If you go into the woods and stutter, an owl is likely to turn up. At which point you can interrogate it, argue with it, and perhaps liberate it from its own mental and behavioural habits.

Maybe, by stuttering a new poetic syntax, we can resist and overturn the process by which the owls of officialdom render us incapable of vital speech – establishing for ourselves a renewed (hyphened) identity through the subversive deployment of stories, objects, gestures and actions that are both critical and transformative. By stuttering at the owls of officialdom we might be liberated from the stifling mental and behavioural habits they impose on us, and maybe officialdom will itself be transformed, becoming more open to many voices and stories.

References

Abrams, D. (1997): The Spell of the Sensuous, New York: Vintage Books

Atkinson, D. (2002): Art in Education: Identity and Practice, The Netherlands: Klewer Academic Publishers

Barthes, R. (1990): S/Z, Oxford: Blackwell

cobbing, b., griffiths, b. eds. (1992): Verbi Visi Voco: A Performance of Poetry, London: Writers Forum

cummings, e.e. (1963): selected poems: 1923-1958, London: Penguin

Danvers, J. (1999): Remnants, artist’s book, limited edition

Danvers, J. (2003): Towards a Radical Pedagogy: Provisional Notes on Learning and Teaching in Art and Design, The International Journal of Art and Design Education, 22(1) Eco, U. (1989): The Open Work, Harvard University Press

Flam, J. ed. (1996): Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press

Perloff, M. (1996): Wittgenstein’s Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Perry, S. ed (2002): Coleridge’s Notebooks: A Selection, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Rorty, R. (1999): Philosophy and Social Hope, London: Penguin Books

Rothenberg, J. ed. (1969): Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia & Oceania, New York: Anchor Books

Rothenberg, J., Joris, P. (1995): Poems for the Millennium, Volume One, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press

Rothenberg, J., Joris, P. (1998): Poems for the Millennium, Volume Two, Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press

Internet Sources

Interview with Fred Wah – http://www3.sympatico.ca/pdarbyshire/wah.html – 14/10/2002

Jerome Rothenberg: Ethnopoetics at the Millenium, A Talk for the Modern Language Association, December 29, 1994 – http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/rothenberg/ethnopoetics.html – 02/10/2002